The Radiant Falcon

By Jon Engelsman

October 11, 2021

On the incomplete history of the Radiant Falcon, a former U.S. Army intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance aircraft, and a look at some of its advanced sensing technology developed at U.S. research laboratories.

A Forgotten Bird of Prey

This is a story about a US military surveillance aircraft that no longer exists. It started out life as a normal airplane, was laden with advanced sensors and then flew, however briefly, over the skies of Iraq and Afghanistan. It was tasked with hunting hidden explosives and those who hid them.

But only one of its kind ever flew. It may have inspired the design or operation of other surveillance aircraft, or it may have been a technological dead-end. Not much information about this particular aircraft seems to exist, so I do not know which one it is.

But its story is still worth telling. Meet the Radiant Falcon.

The Radiant Falcon (N1000) at Norwich Aiport, 2012

Image: © Matt Varley (used with permission)

The Radiant Falcon (N1000) at Norwich Aiport, 2012

Image: © Matt Varley (used with permission)

Eyes in the Sky

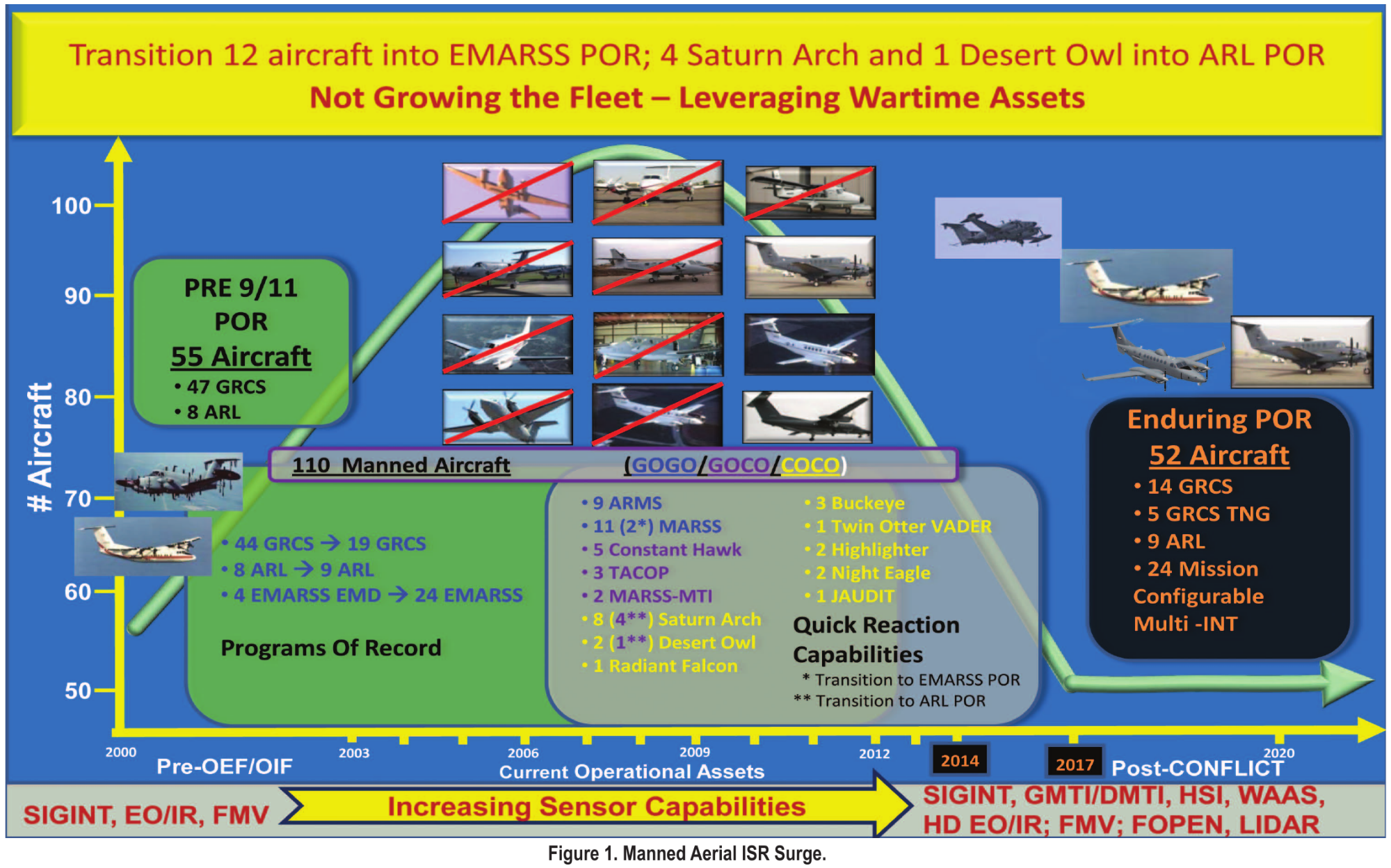

Throughout the early and mid 2000’s, the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq led to a high demand for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) operations throughout the U.S. military. The U.S. Army in particular invested heavily in developing new sensing technologies and new ISR platforms that met the specific needs of counter-terrorism and counter-IED operations.

As combat operations in U.S. Central Command increased from 2001 to 2011, so did maneuver commanders’ demand for additional ISR capabilities. INSCOM met the demand with an “ISR surge” and developed new sensor technologies under a rapid fielding approach called quick reaction capabilities (QRC).

U.S. Army/MI Professional Bulletin, July-September 2018

This “ISR surge” included funding for new technologies and new aircraft, allowing the U.S. Army to grow their airborne intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (AISR) fleet to a peak of 110 crewed aircraft by 2010. The specific demands of counter-IED operations required new types of sensing capabilities, relying not just on established signals intelligence (SIGINT) and electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) surveillance capabilities leftover from the Cold War era, but now incorporating new types of aerial sensing technologies like wide-area aerial surveillance (WAAS), hyerspectral imagery (HSI) and new applications of synthetic aperture radar (SAR).

Image: U.S. Army, MIPB, 2014

Image: U.S. Army, MIPB, 2014

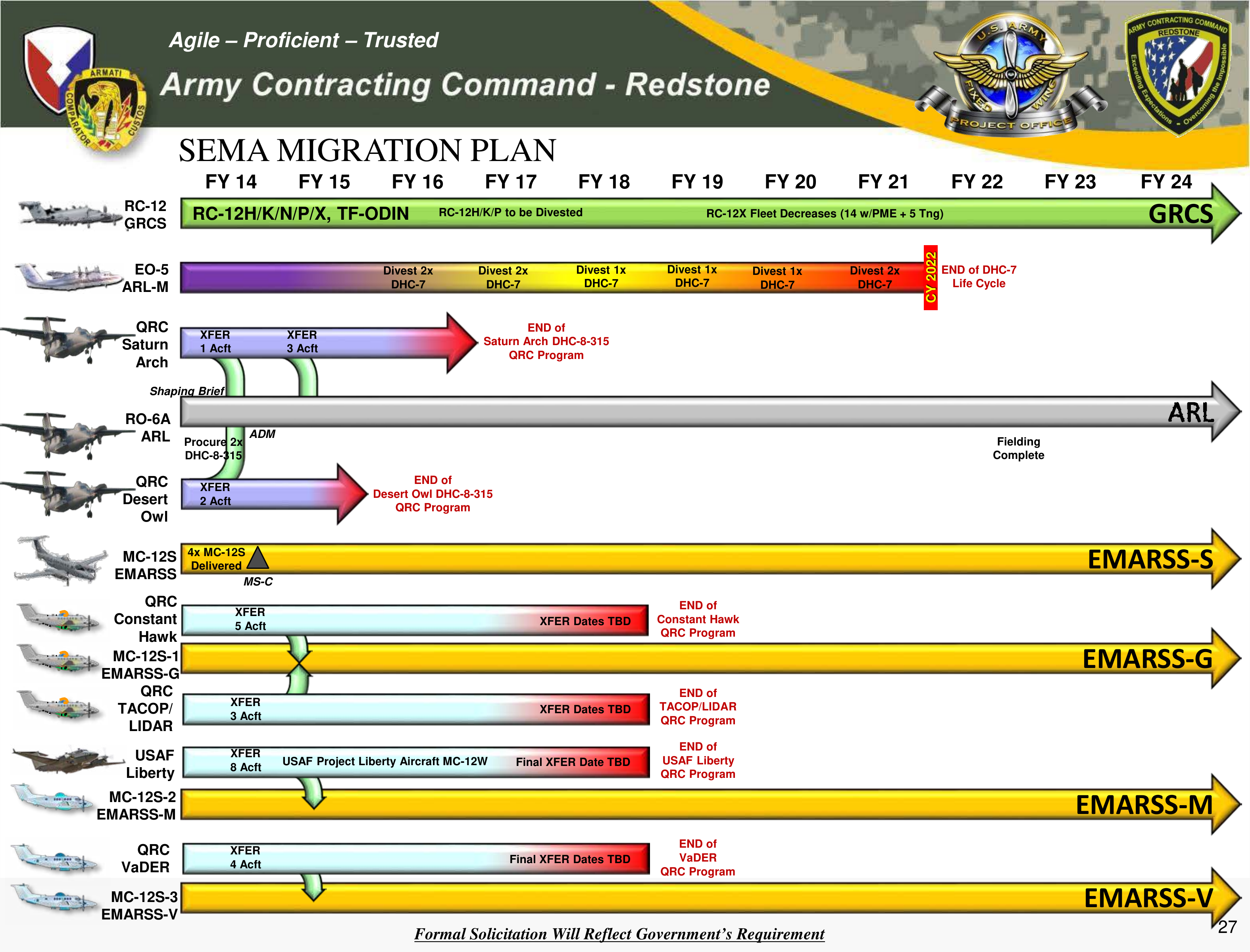

Along with legacy ISR platforms like the Guardrail Common Sensor (GRCS), Airborne Reconnaissance Low (ARL) and the Enhanced Medium Altitude Reconnaissance and Surveillance System (EMARSS), the U.S. Army also brought to the field new quick reaction capabilities (QRC) with platforms like Saturn Arch and Desert Owl that offered unique capabilities for the counter-terrorism era.

With this equipment on board, both types of planes had the mission of performing persistent surveillance missions across relatively wide areas, using their sensors to build larger maps of entire regions. From there, analysts could examine the imagery for items of interest, potentially establishing so-called “patterns of life” for specific terrorists or small groups of militants...The Army primarily employed them to hunt for improvised explosive devices and, by extension, to trace insurgent movements back to bomb workshops or other base camps.

The Drive/Joseph Trevithick, 2018

At its peak, the U.S. Army had over fifty of these QRC aircraft in operation, including multiple Desert Owl and Saturn Arch aircraft. But while it seemingly offered similar capabilities to these two platform types, only one Radiant Falcon was ever built.

An Origin Story

The story of the Radiant Falcon likely started sometime between 2008 and 2009, born out of the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL), part of the Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC) within the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Its design and development was funded by JIEDDO, the Joint IED Defeat Organization which was tasked with identifying and funding new counter-IED efforts throughout the Department of Defense. To build the Radiant Falcon, the ERDC turned to the defense contractor duo of Dynamic Aviation and Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC, now known as Leidos), a joint team who had also been involved with other JIEDDO-funded ERDC efforts like the Desert Owl and Saturn Arch programs.

Based out of Bridgewater, Virginia and tasked as the platform integrator, Dynamic Aviation sourced a 1985 De Havilland Canada DHC-8 (known as a Dash 8) as the Radiant Falcon’s base airframe, opting for the smaller DHC-8-102 variant of the Dash 8. Dynamic Aviation registered this aircraft as N1000 on May 23rd 2009 via an apparent subsidiary (Dynamic Avlease Inc).

DHC-8-102

Image: Dynamic Aviation

DHC-8-102

Image: Dynamic Aviation

N1000 was then heavily modified from its original configuration with a suite of sensor technologies and supporting equipment in order to transform the aircraft into a fully-operational ISR platform: the Radiant Falcon.

Radiant Falcon

Image: Unknown, via Twitter

Radiant Falcon

Image: Unknown, via Twitter

The resulting unusual features are visually reminiscent of some other heavily-modified Dash 8’s, such as the US Air Force’s E-9A Widget or the U.S. Army’s RO-6A ARL-E platform. But the most striking similarity the large extended nose of Canada’s CT-142 Gonzo aircraft.

(clockwise, from top left): E-9A Widget, RO-6A ARL-E, CT-142 Gonzo

(clockwise, from top left): E-9A Widget, RO-6A ARL-E, CT-142 Gonzo

To my knowledge, N1000 was the only Radiant Falcon airframe ever built by Dynamic Aviation. While the modifications made to its base DHC-8-102 airframe were unusual, they were driven by the unique constraints of the large ISR technology suite installed on the aircraft.

Under the Wing

Similar to some of the U.S. Army’s other multi-sensor ISR platforms like the Saturn Arch and the RO-6A ARL-E, the Radiant Falcon contained a diverse array of sensors as part of its capable ISR suite. This sensor suite included a mix of EO/IR imaging and full-motion video, hyperspectral imagery, multiple synthetic aperture radar systems and possibly even signals intelligence (SIGINT) systems with geolocation/direction-finding capabilities.

Image: USACE, ERDC, 2011

Image: USACE, ERDC, 2011

(Don’t let this graphic fool you with the reversed image of an E-9A Widget aircraft. That is not in fact the Radiant Falcon!)

First, like many other ISR platforms, the Radiant Falcon carried a standard L3-Wescam MX-20 electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) sensor that provided general targeting and surveillance capabilities, including full-motion video (FMV). This sensor was mounted on a retractable turret in a right-side sponson on the aircraft.

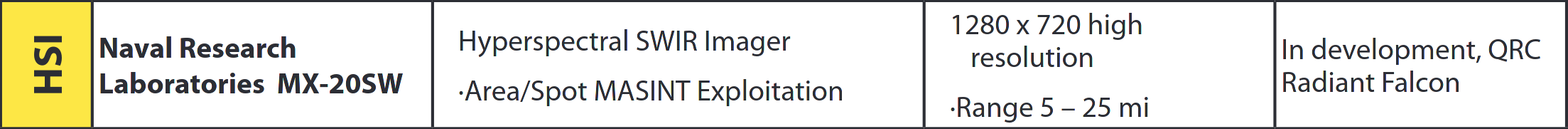

Next, an unusual variant of this imaging sensor, the MX-20SW hyperspectral imager (HSI) providing short-wave infrared (SWIR) imaging, was similarly mounted on a retractable turret in a sponson on the opposite left-side of the aircraft.

MX-20SW, a short-wave infrared hyperspectral imager

MX-20SW, a short-wave infrared hyperspectral imager

Originally developed by the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) and presumably handed off to L3-Wescam for production, the MX-20SW sensor was primarily used to collect measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT) at ranges up to 25 miles.

Source: U.S. Army

Source: U.S. Army

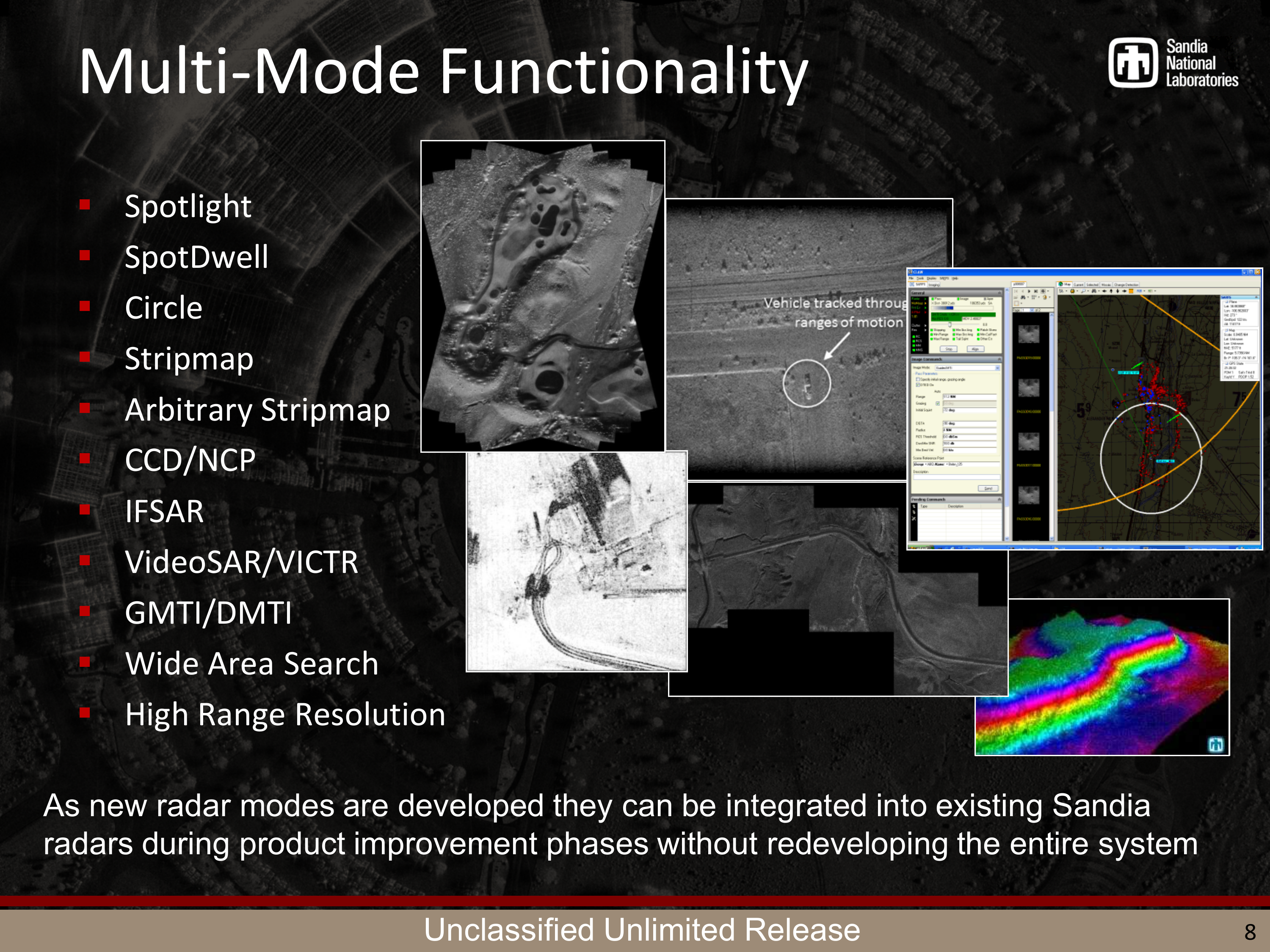

A Ku-band synthetic aperture radar (SAR) was also included in the Radiant Falcon’s sensor suite. This system was developed by the Department of Energy’s Sandia National Labs, likely as part of their Facility for Advanced RF and Algorithmic Development (FARAD), and then delivered to SAIC/Dynamic Aviation in 2010.

Source: Dept. of Energy/NNSA

Source: Dept. of Energy/NNSA

Sandia National Labs has an extensive history in developing new SAR technology, like the MiniSAR system for the Army’s Copperhead program and the Lynx SAR radar, now built by General Atomics and deployed on the Predator platform.

It’s unclear exactly what kind of capabilities the Radiant Falcon’s Ku-band SAR system provided, but based on the nature of its counter-IED mission those capabilities likely included Coherent Change Detection (CCD), Normalized Coherent Product (NCP) and maybe even VideoSAR.

Image: Sandia National Laboratories

Image: Sandia National Laboratories

A passive antenna and a geolocation system were also included as part of the Radiant Falcon’s sensor package. It’s unclear what exact capabilities these systems provided, but it’s possible that the passive antenna offered some form of signals intelligence (SIGINT) collection, while the “geolocation system” was likely used to provide some type of direction-finding capabilities for those collections.

An ultra-high frequency (UHF) SAR system rounded out the sensing technologies onboard the Radiant Falcon. UHF SAR systems were often used as foliage-penetrating (FOPEN) radars to identify objects through dense foliage, such as IED’s or the buried control wires used to detonate them. This UHF SAR system, if not its processing systems, was likely developed by MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory.

And finally, multiple racks of supporting equipment were also integrated into the aircraft, consisting of “raids, KVMs, PDUs, GPS Splitter, Force 10 / Cisco switches, Winchester Servers, [and a] Digital Timing Generator”, likely used to process and analyze the huge amounts of complex data generated primarily by the Ku-Band and UHF SAR systems.

All together, this ISR technology suite was integrated into various points on the Dash 8 airframe. Some of the sensors were mounted on retractable turrets ( close-up here), including the Ku-Band SAR system installed in the aircraft’s extended nose and the MX-20 and MX-20SW sensors in two offset side sponsons, while the UHF SAR and passive antenna were likely mounted in two large pods underneath the aircraft.

Operations

Once fully developed and built, the Radiant Falcon was deployed to the Middle East sometime around 2010 or 2011 and was apparently based at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan. As a quick-reaction capability (QRC) for the U.S. Army, it acted as a contractor-owned, contractor-operator (COCO) platform.

As the owner, Dynamic Aviation provided a forward-deployed maintenance crew for the Radiant Falcon at Bagram. As the operator, SAIC (now Leidos) provided the civilian flight crew for the aircraft consisting of the pilots, airborne sensor operators and imagery analysts. This crew was responsible not only for operating the aircraft and its sensors, but also for coordinating the Radiant Falcon’s counter-IED operations with the U.S. Army and Task Force ODIN.

Thomas Stanko, a civilian contractor with SAIC, said when he deploys, he’ll be doing counter-improvised explosive device missions from an aircraft known as Radiant Falcon. “The U.S. Army is our primary customer, but we support all troops on the ground,” said Stanko. “Our mission is to detect IEDs from the air and pass that information to the route clearing teams on the ground so they can negate, dismantle or destroy them.”

USMC; August 10th 2011

While its full operational history is unknown, an image of the Radiant Falcon taken on September 11th 2011 shows what is likely the maintenance and operating crew for the aircraft at a forward-deployed location.

Unknown location, 2011

Image: via LinkedIn

Unknown location, 2011

Image: via LinkedIn

The only known official image of the Radiant Falcon seemingly first appeared on the cover of a February 2012 issue of Jane’s Defence Weekly, apparently provided by Dynamic Aviation. This same image later appeared in a 2020 Janes article on the U.S. SOCOM Tactical Airborne Multi-Sensor Platform (STAMP), yet another secretive Dash 8 ISR platform.

Radiant Falcon

Image: Janes via Dynamic Aviation

Radiant Falcon

Image: Janes via Dynamic Aviation

Few other images of the Radiant Falcon are known to exist. But throughout 2011 and 2012, the Radiant Falcon (N1000) was apparently spotted at a number of European airports. First, it was seen at Germany’s Stuttgart Airport in November 2011. Seven months later in July 2012, it was spotted at Wick Airport in Scotland and then again at Stuttgart, where it was now joined by some notable company, including a CIA-linked Casa/IPTN CN-235 and another Dynamic Aviation-registered Dash 8 (N8300L, presumed to be at the time a Saturn Arch platform but now converted to an RO-6A ARL-E). A few months later on November 29th 2012, N1000 was also spotted at Hungary’s Ferenc Liszt airport.

That same day, the Radiant Falcon flew on to England’s Norwich Airport where it stayed the night and then took off the next day, offering a closeup view for local planespotters.

N1000 at Norwich Airport, November 29th 2012

Image: © Matt Varley (used with permission)

N1000 at Norwich Airport, November 29th 2012

Image: © Matt Varley (used with permission)

There are a few observations worth nothing here. Having now been deployed and operational for roughly one to two years, the Radiant Falcon had collected a few mission markings from its counter-IED operations.

N1000 at Norwich Airport, November 29th 2012

Image: © Matt Varley (used with permission)

N1000 at Norwich Airport, November 29th 2012

Image: © Matt Varley (used with permission)

These mission marks showed nine cartoon bombs, with two of them having lit fuses and crossed-out eyes, presumably representing explosive devices that had been detected by the Radiant Falcon but still possibly detonated.

IED mission marks

Image: @162154_VRC40

IED mission marks

Image: @162154_VRC40

Another image of N1000 provided a better angle of the large belly-mounted pod with what appears to be an array of external antennas.

N1000 at Norwich Airport, November 29th 2012

Image: © Matt Varley (used with permission)

N1000 at Norwich Airport, November 29th 2012

Image: © Matt Varley (used with permission)

It’s possible that this antenna array is the UHF synthetic aperture radar developed by MIT Lincoln Laboratory and used for foliage-penetrating imaging.

Belly-mounted UHF synthetic aperture radar?

Belly-mounted UHF synthetic aperture radar?

An image of N1000 taking off shows some other external antennas, used either for communications or possibly signals intelligence (SIGINT). Also noticeable here is that by this time in 2012, the secondary large pod mounted under the tail had been removed. This pod possibly contained the “passive antenna” noted earlier, or maybe some other sensing system, but its actual purpose and the reason for its removal is unknown.

N1000 at Norwich Aiport, 2012

Image: © Matt Varley (used with permission)

N1000 at Norwich Aiport, 2012

Image: © Matt Varley (used with permission)

This visit to Norwich Aiport in 2012 is notable as it offered some of the best available images of the Radiant Falcon (N1000). There are a few additional photos taken at airports around this same time, but I’ve been unable to find any photos of the Radiant Falcon after 2012.

End of the Line

After operating since at least 2010, the ERDC handed off the Radiant Falcon and other counter-IED platforms to the U.S. Army’s Aviation Branch by the end of 2014.

In the interval between 2006 and 2014, in support of numerous U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) Joint Urgent Operation Needs Statements, ERDC engineers and research teams led whole-of-government and industry teams in developing more than six major quick reaction capability (QRC) programs that were formerly recognized by the Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat Organization (JIEDDO) and CENTCOM as effective counter-IED (C-IED) systems. The total ERDC QRC resource execution in this period exceeded $2 billion. Airborne systems included Saturn Arch, Desert Owl, Copperhead and Radiant Falcon, all of which were transitioned to Army Aviation by the close of 2014.

Senate Hearing 115-604, May 3rd, 2017

It was around this time that the Desert Owl and Saturn Arch platforms were slated to transition from QRC programs into the official program of record (POR) for the U.S. Army’s RO-6A / Airborne Reconnaissance Low - Enhanced (ARL-E) platform. However, the Radiant Falcon program was notably absent from such plans at the time.

Image: U.S. Army, Fixed Wing Project Office, 2015

Image: U.S. Army, Fixed Wing Project Office, 2015

Whether due to technological obsolesecence or merely a redudancy in capability with these other programs, the fate of the Radiant Falcon was sealed and by 2014 it was officially on the budgetary chopping block.

The Army is also eliminating 55 Joint Improvised Explosive Defeat Device Office (JIEDDO) force protection systems with an annual sustainment cost of $328.4 million. Some of the major commercial off-the-shelf JIEDDO systems eliminated include: Hawkeye ($60 million); Radiant Falcon ($48 million); Sand Dragon ($45 million); and Gator ($15 million).

Senate Hearing 113-465, 2014

With its future already decided, the Radiant Falcon (a DHC-8-102 with serial number 024) was re-registered by Dynamic Aviation as N8100V in late 2013. By no later than mid-2016, it had even shed its unique Radiant Falcon configuration.

As of 2020, N8100V could still be found at Dynamic Aviation’s headquarters at Bridgewater Air Park, now just an unassuming Dash 8 with few signs of its former radiant self.

N8100V at Bridgewater Air Park, 2020

Image: © Owen O'Rourke (used with permission)

N8100V at Bridgewater Air Park, 2020

Image: © Owen O'Rourke (used with permission)

The current or future fate of N8100V remains unclear. As one of the shorter 100 series Dash 8 variants, it’s unlikely to be converted to either an RO-6A ARL-E platform or the even more secretive STAMP platform, both of which seem to prefer the more powerfull 200 series or the longer 300 series variants. But with Dash 8 aircraft in increasingly high demand as military ISR platforms, N8100V may yet fly again.

A Story Worth Telling

Whatever the future holds for N8100V, the Radiant Falcon as it was will never fly again. Built for a specific point in time during the height of the IED threat in Iraq and Afghanistan, its mission has come to an end.

With only one ever having been built, it’s not clear whether or not the U.S. Army considered the Radiant Falcon a successful platform or not. Other QRC platforms, like the Desert Owl and Saturn Arch, were apparently deemed worthy of adoption into the current ARL-E platforms but the Radiant Falcon didn’t seem to share that fate. Its influence on past or future ISR programs, if any, is unknown.

But the fact that even one Radiant Falcon was built and that it even flew for those short few years means that it still has a story to tell. Maybe one day we’ll know more about the Radiant Falcon.

- Posted on:

- October 11, 2021

- Length:

- 13 minute read, 2765 words

- See Also: