Victor Hanson

A son of immigrant Swedish farmers who died fighting in the Argonnes forest with the 308th Infantry Regiment and the Lost Battalion.

Growing Up in Minnesota

Victor Edgar Hanson was born on July 14th 1983 in Wyanett, Minnesota, a small community outside the town of Princeton and about 60 miles north of Minneapolis.

His mother Christina was a Swedish immigrant who came to the United States in 1875, residing first in Duluth, Minnesota for two years before marrying another Swedish immigrant, Hans Hanson, in the nearby town of Thompson. The married couple would eventually make their way south towards Minneapolis, settling on a farm in Blomford in Isanti County. Sell that farm in 1891, they would move down to the small community of Wyanett, residing on a new farm near Green Lake.

Two years later after they had settled on the farm, Victor was born. One of eight children, he likely spent most of his time working on the family farm. He would also spend time cutting wood on his buzz saw, going up north to Mizpah or Skibo during the winter and Duluth in the spring or visiting the nearby town of Cambridge.

The Draft

In 1914, the Great War in Europe had started. Three years later, the United States would pass the Selective Service Act of 1917, the start of the American military draft during World War I.

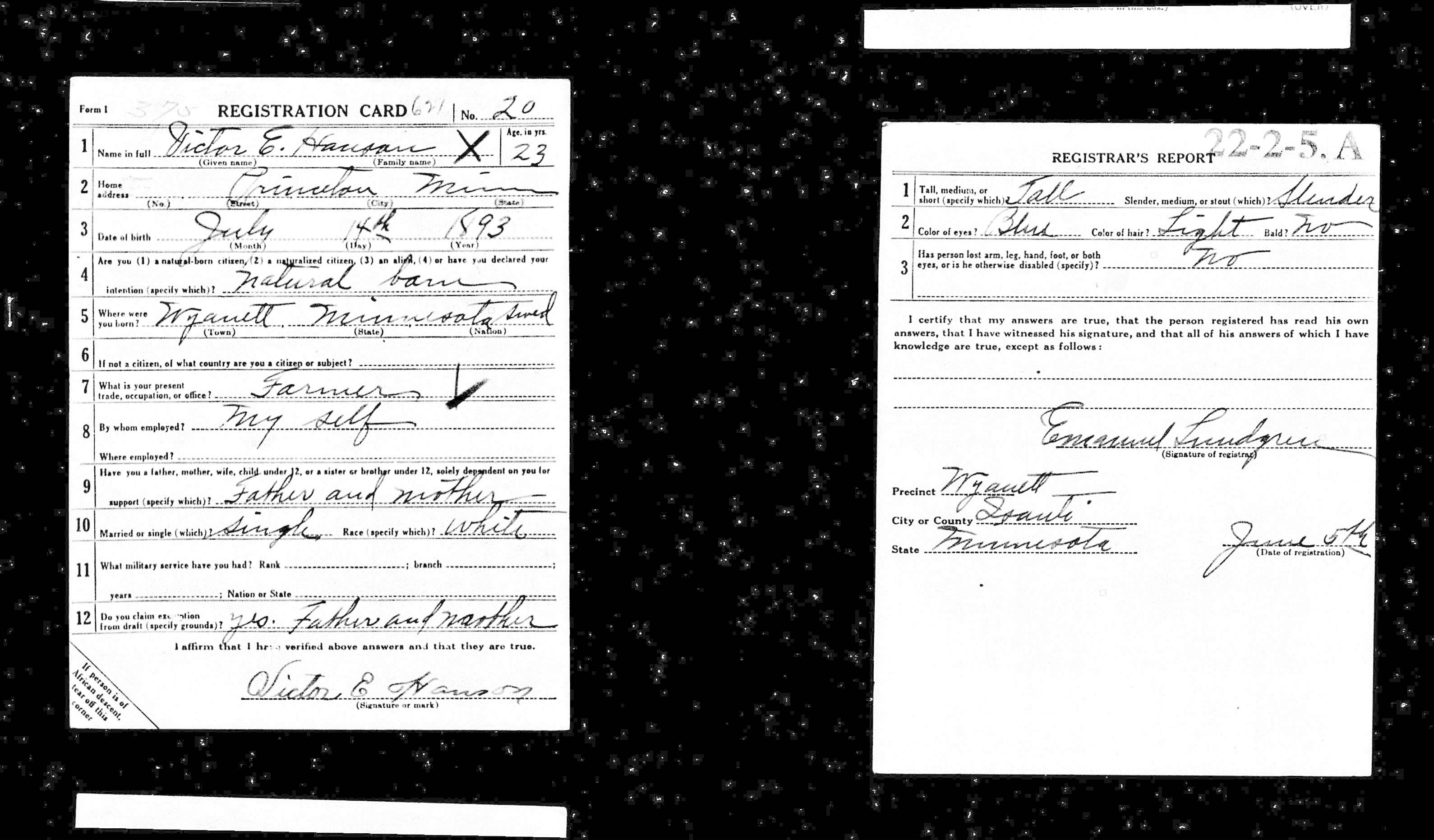

About three weeks later, Victor Hanson registered for the draft in the Wyanett precinct of Isanti County, Minnesota on June 5th 1917, a little over one month shy of his 24th birthday.

Victor Hanson, WWI Draft Registration Card

Victor Hanson, WWI Draft Registration Card

He claimed an exemption from the draft because he was responsible for supporting his mother and father as a farmer, although the exemption would not be granted.

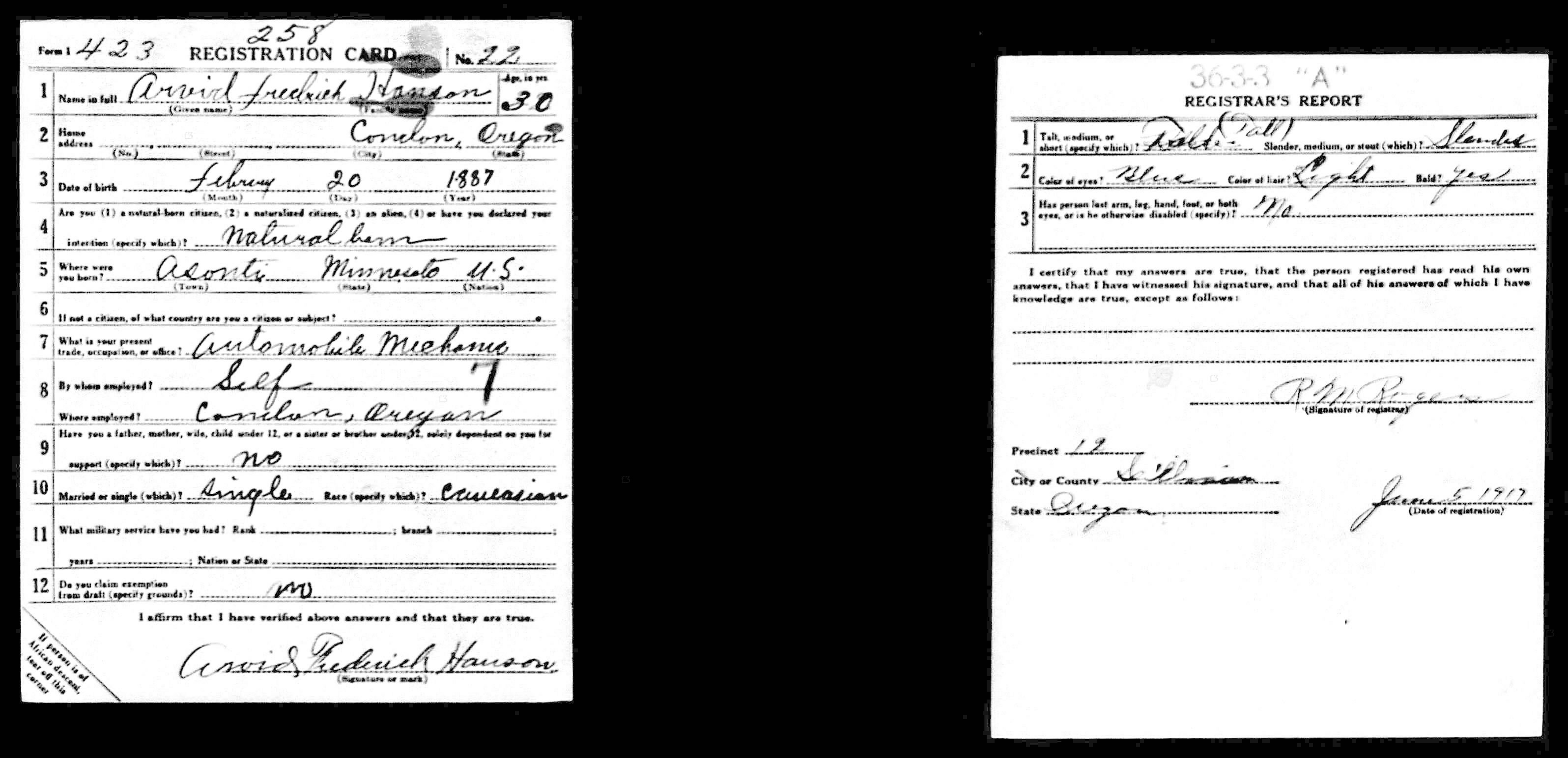

At the same time, his older brother Arvid Hanson, working as an automobile mechanica in Condon, Oregon, would also register for the draft.

Arvid Hanson, WWI Draft Registration Card

Arvid Hanson, WWI Draft Registration Card

A Move to Bellevue

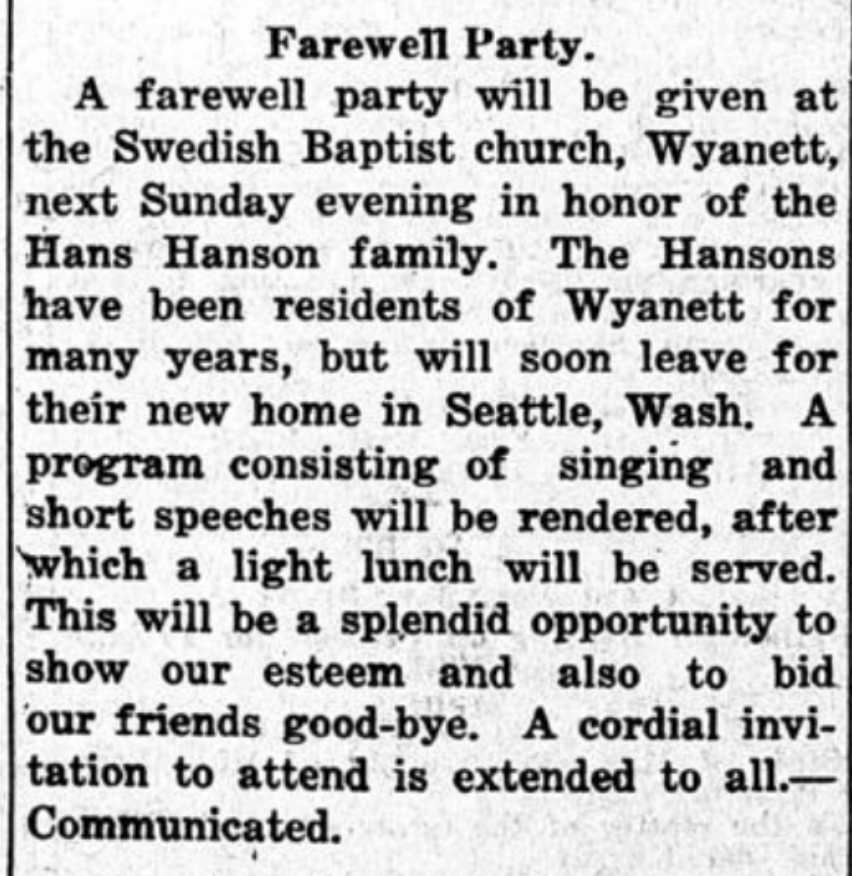

In early 1918, the Hanson family would decide to leave Minnesota and head out west to Seattle, Washington. Neighbors in their small community of Wyanett threw the family a farewell party to say goodbye.

The Princeton Union, February 21st 1918

The Princeton Union, February 21st 1918

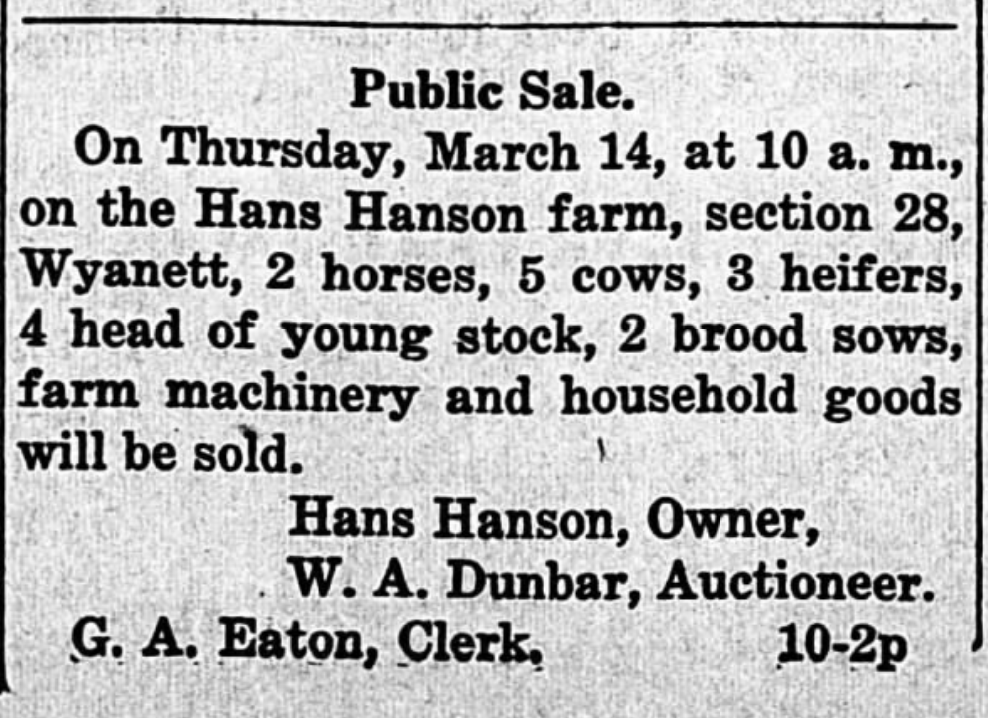

The following month, Victor’s dad Hans Hanson put the family farm up for auction, including the animals, machinery and household goods.

The Princeton Union, March 7th 1918

The Princeton Union, March 7th 1918

Hans and Christina, and possibly some of their younger children, would then make the long trek west, moving to Bellevue, Washington that same year. It’s unclear why the Hanson family left the state of Minnesota and chose to settle in Bellevue, although it’s possible they were moving to be closer to their sons George and Arvid were likely already living in either Oregon or Washington at the time.

Joining the Army

On June 27th 1918, Victor would be called to duty in the US Army and begun training at Camp Lewis in Pierce County, Washington. It’s unclear if he was still in Minnesota at this time or if had already moved to Washington with his family. If he had been in Minnesota, he likely would have first reported at the National Guard armory depot in Olivia, Minnesota before taking a train out west to Camp Lewis, Washington about 50 miles south of Bellevue.

After a few weeks of training, he and 10,000 other recruits were sent to Camp Kearny in San Diego to join the US Army’s 160th Infantry Regiment, part of the 80th Infantry Brigade in the 40th “Sunshine” Division of California. Less than a month after joining the Army, Victor and the 40th Division would be on trains headed to the East coast on the first step of their journey to the war in Europe.

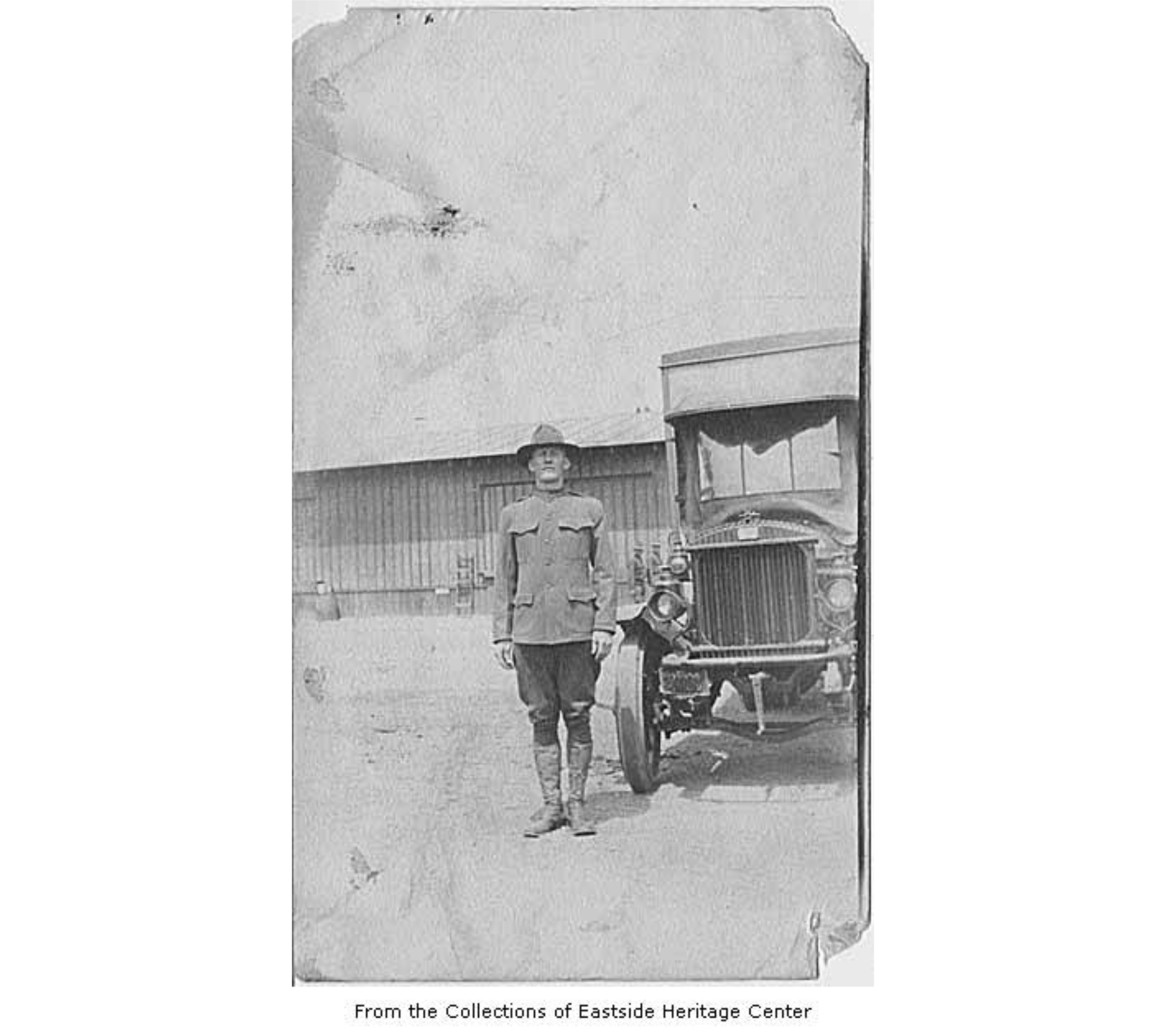

Victor Hanson, 1918, c/o Eastside Heritage Center

Victor Hanson, 1918, c/o Eastside Heritage Center

Heading to France

After a six day train ride from California, the 40th Division arrived at Camp Mills in Long Island, New York on August 1st 2018. After one week, Victor and 14,000 other soldiers in the 40th Division would set sail from the Port of Hoboken, New Jersey on August 8th.

At this point, Victor was a Private in Company M (ASN 3139387), part of the 160th Infantry Regiment, 80th Infantry Brigade. Only a few days after arriving at Camp Mills, the 80th Infantry Brigade would set sail for Europe leaving from Brooklyn, New York.

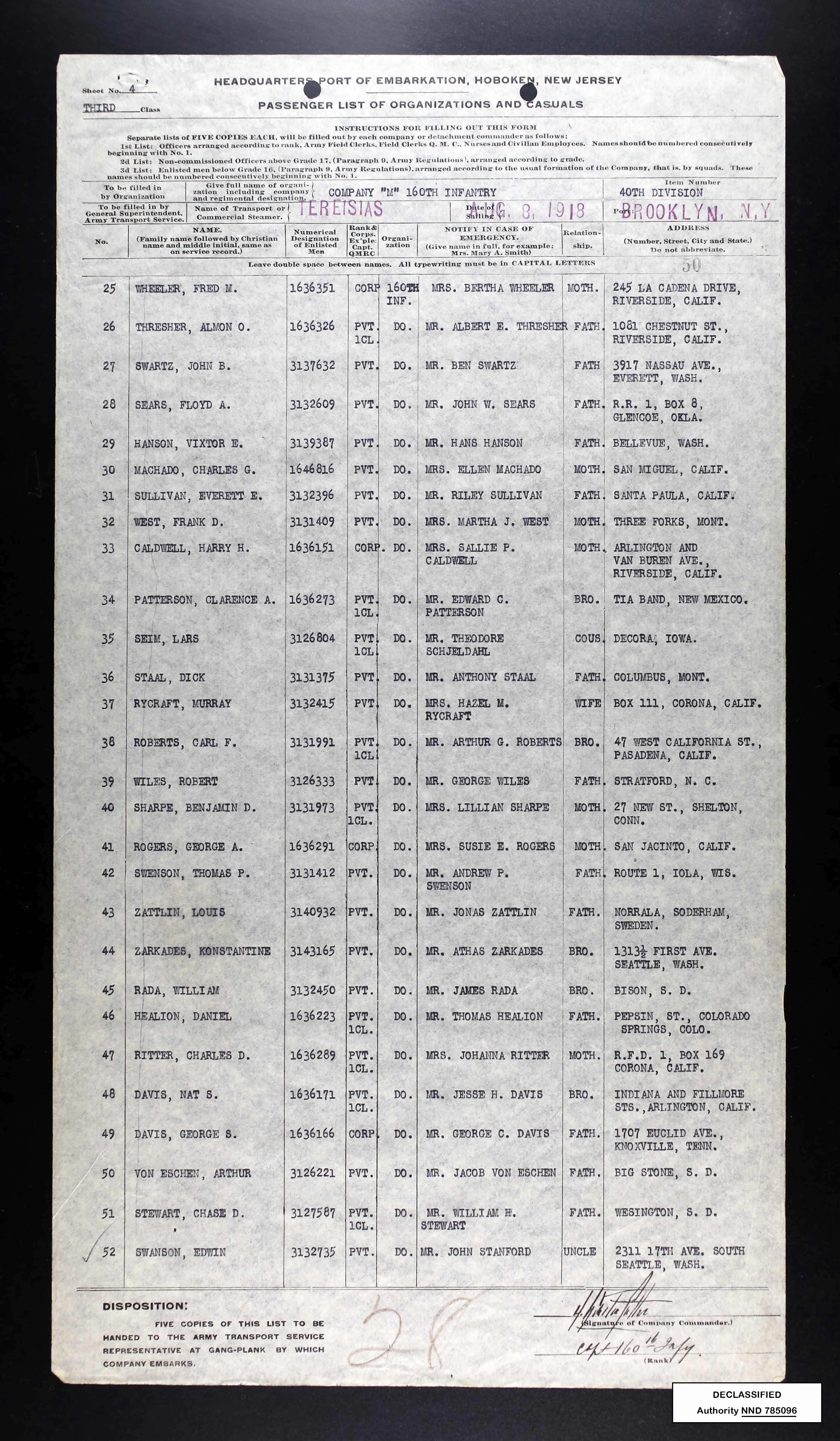

Passenger list of the ship Tereisias sailing in August 1918

Passenger list of the ship Tereisias sailing in August 1918

Note: Victor appears to have been misspelled as Vixtor.

Victor and 1,200 other soldiers would sail on the British-built troop transport ship Tereisias, part of a 12-ship convoy carrying the 14,000 members of the 40th Division to Europe.

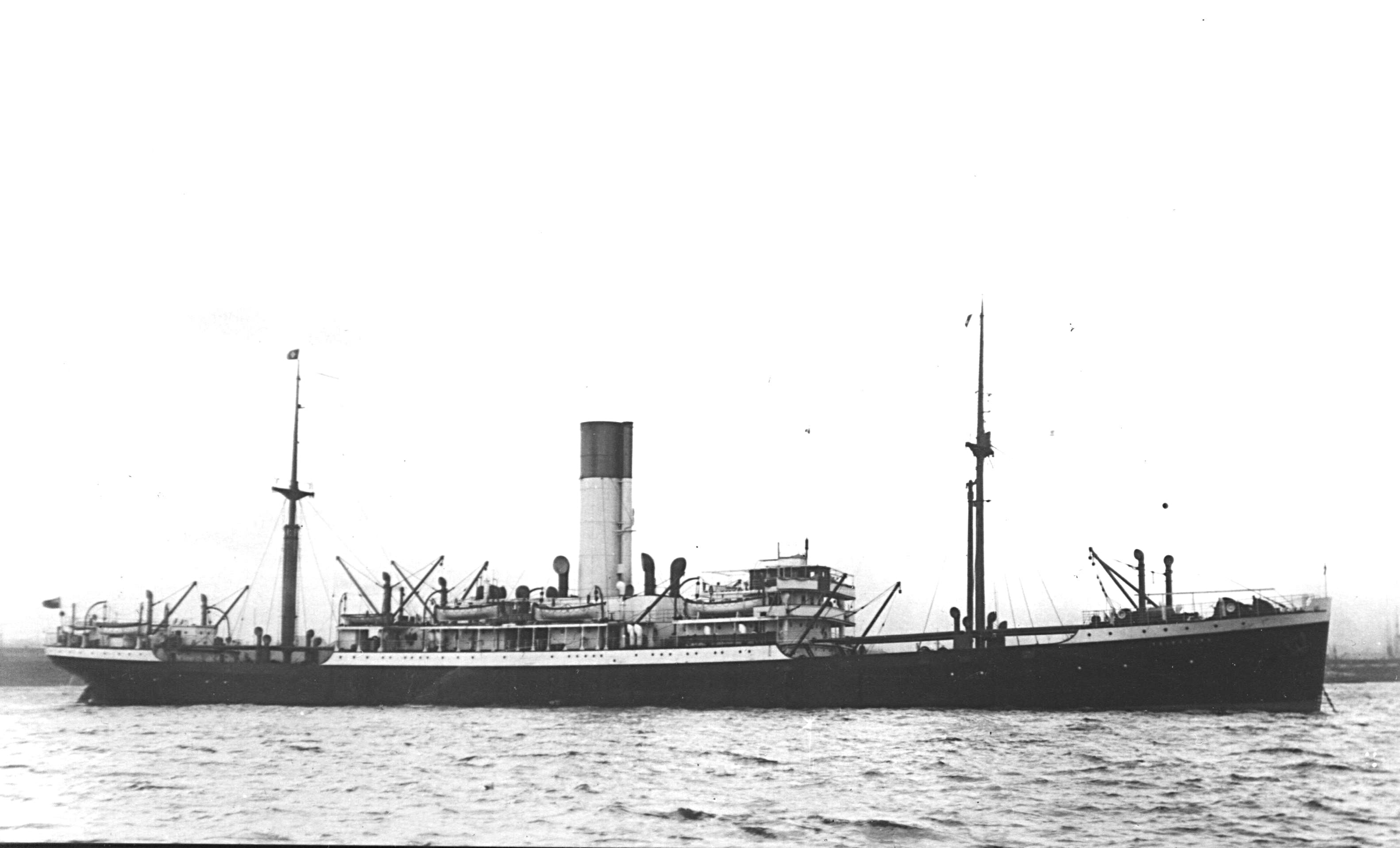

Transport ship Tereisias, 1915, c/o The Allen Collection(

Transport ship Tereisias, 1915, c/o The Allen Collection(

On their journey across the Atlantic, the convoy would be accompanied by the US Navy cruiser USS Rochester and the recently commissioned destroyer USS Wickes, protecting the lives of over 20,000 American soldiers in total.

Arriving in Europe

After a 12-day journey, the ship convoy carrying the 40th Division would arrive in Liverpool, England without incident on August 20th 1918 at 0800.

After a few brief marches over the next couple of days, the 80th Infantry Brigade arrived in Winchester, England and boarded the SS Queen Alexandra on August 24th. The following morning, they arrived at the port of Cherbourg on the western coast of France. After a brief stop at a British rest camp, they would travel over 400 km by train to the town of Cher in central France on August 27th 1918.

The following day, the 40th Division would be reorganized as the 6th Depot Division, one of six divisions that would provide training for replacement troops to be sent to the front.

After a few weeks of training, Victor and 4,000 other men from the 6th Depot Division were transferred to the 77th Division on September 20th 1918.

77th Division

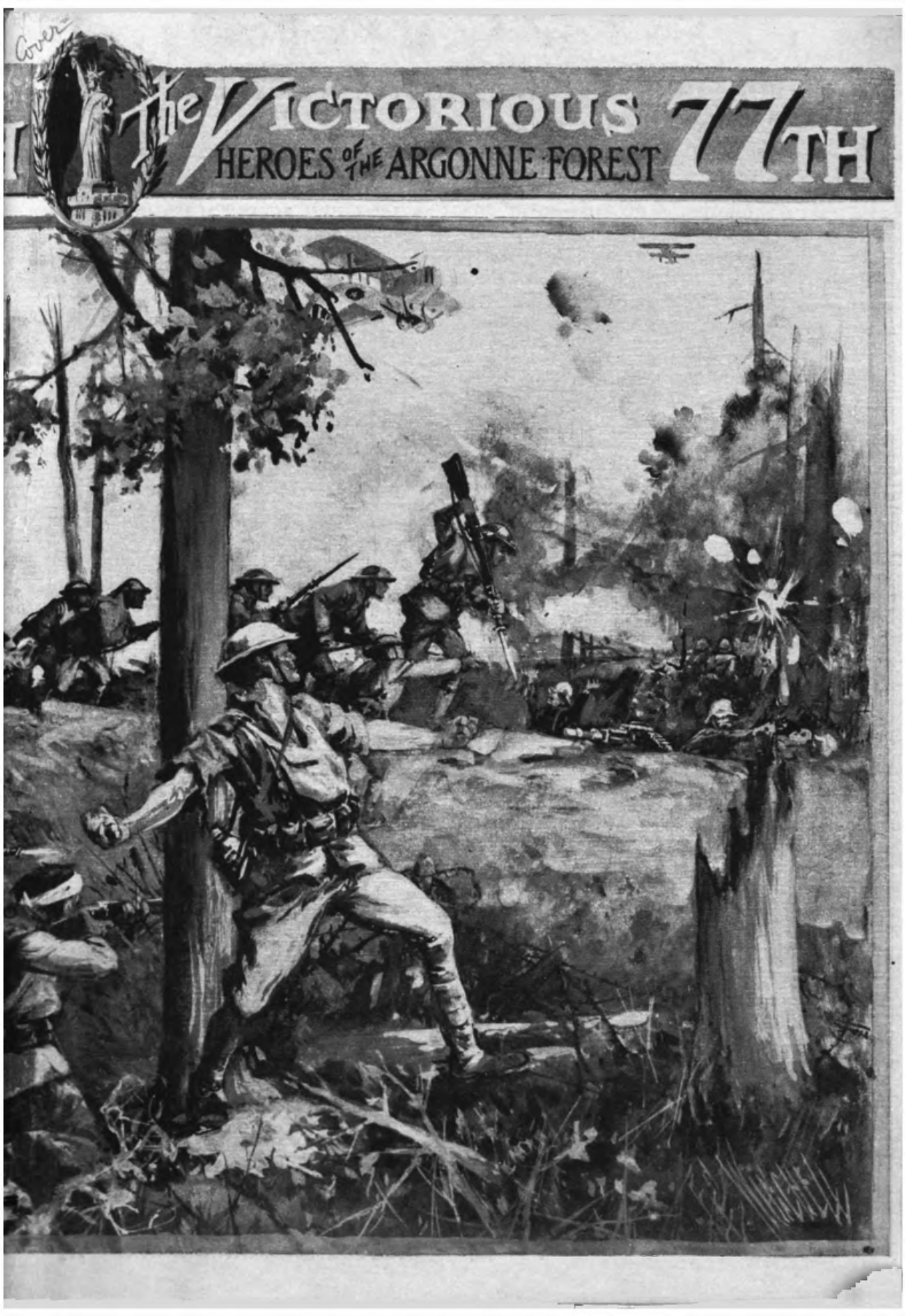

The Victorious 77th Division (New York's Own) in the Argonne Fight

The Victorious 77th Division (New York's Own) in the Argonne Fight

The Victorious 77th Division (“New York’s Own”) was the first division of draftees in the US Army to be sent to the front lines of World War I. They had left New York and arrived in Europe by April 1918, spending the next few months training in France. By the end of June, the 77th had relieved the 42nd Division in northeastern France, serving along the front in the Baccarat sector near the borders of Germany and Switzerland in the former Lorraine region (now Grand Est).

The 77th would spend one month in this quiet sector continuing their training and fighting nearly continuous engagements with the German army. By the end of July however, they would be relieved by the 37th Division and head northwest to Vesle, France, only to spend the following month fighting in the Battle of Fismes and Fismette. They would eventually be relieved by the Italian army in mid-September after additional fighting along the Aisne River.

The 77th Division would spend the next few weeks quietly regrouping itself in eastern France, preparing for its next foray along the southern edge of the Argonne forest. The division’s two infantry brigades, consisting of four regiments including the 308th Infantry Regiment, would start receiving replacement troops for the men they had lost during the previous months of battle.

It would be during this time that Victor and 4,000 men from the 6th Depot Division would join the depleted ranks of the 77th.

308th Infantry Regiment

The 308th Infantry Regiment consisted of almost 4,000 officers and enlisted men across its regimental headquarters, three infantry battalions, a medical detachment and a machine gun company. A battalion included four companies of soldiers, each of which included over 250 officers and enlisted men.

After months in battle as part of the 77th Division, the 308th Infantry Regiment would receive some 1,250 replacement troops provided by depot divisions made up of the former 40th and 41st Divisions, more than a quarter of their full-strength troop count. These replacement troops had no experience in battle and had received only a few months of training in the military, with some men not knowing how to use a hand grenade or work the magazines of their rifles.

As a soldier in this group of replacement troops, Pvt Victor E. Hanson was assigned to Company H, 2nd Battalion of the 308th Infantry Regiment, part of the 154th Infantry Brigade in the 77th Division, entering their ranks on or around September 23rd-25th 1918, less than a month after arriving in Europe.

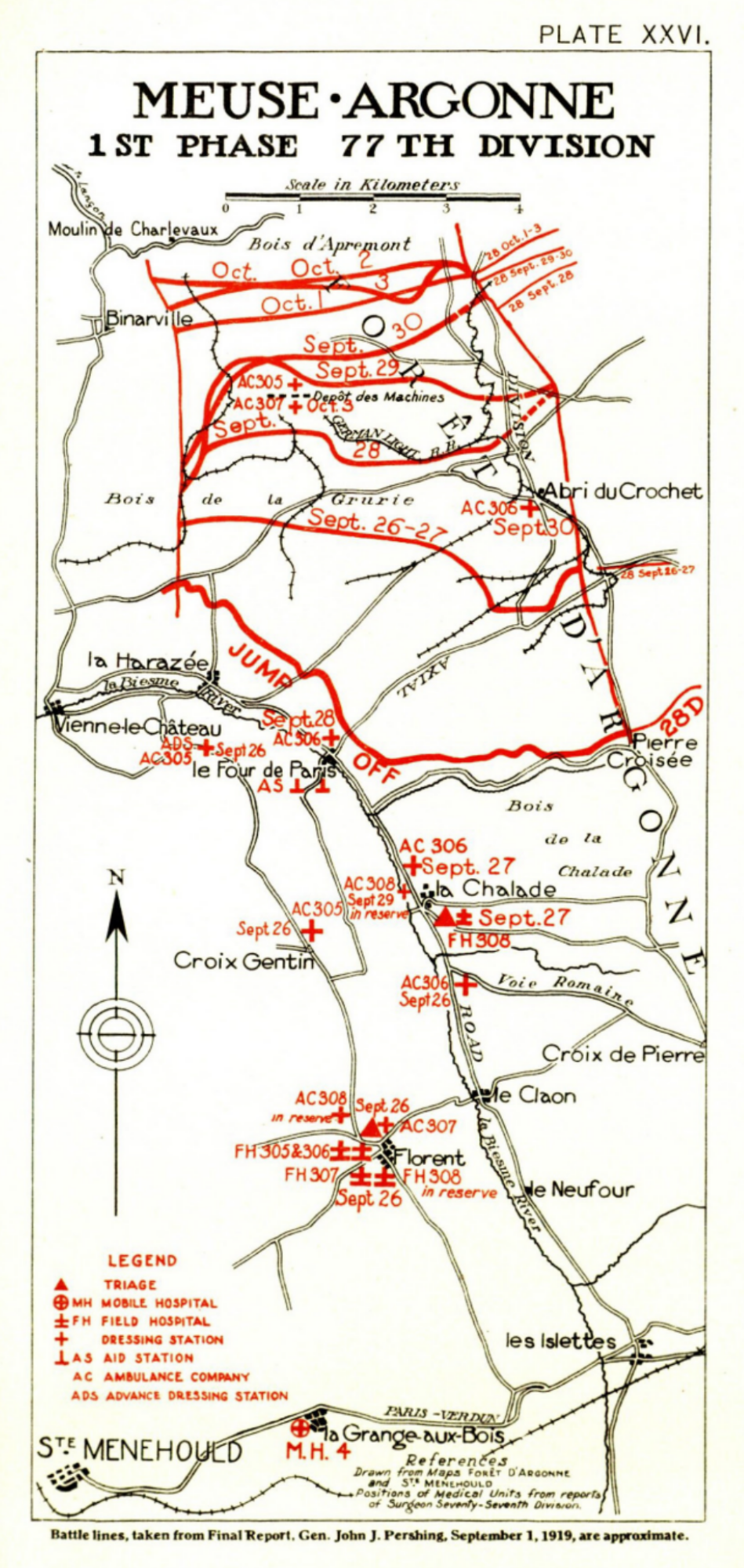

Pvt Hanson likely would have joined the 308th at their staging area in the woods near Florent, on the southern edge of the Argonne forest, a few days before the start of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

The Jump-Off Into the Argonne

The History of the 77th Division

The History of the 77th Division

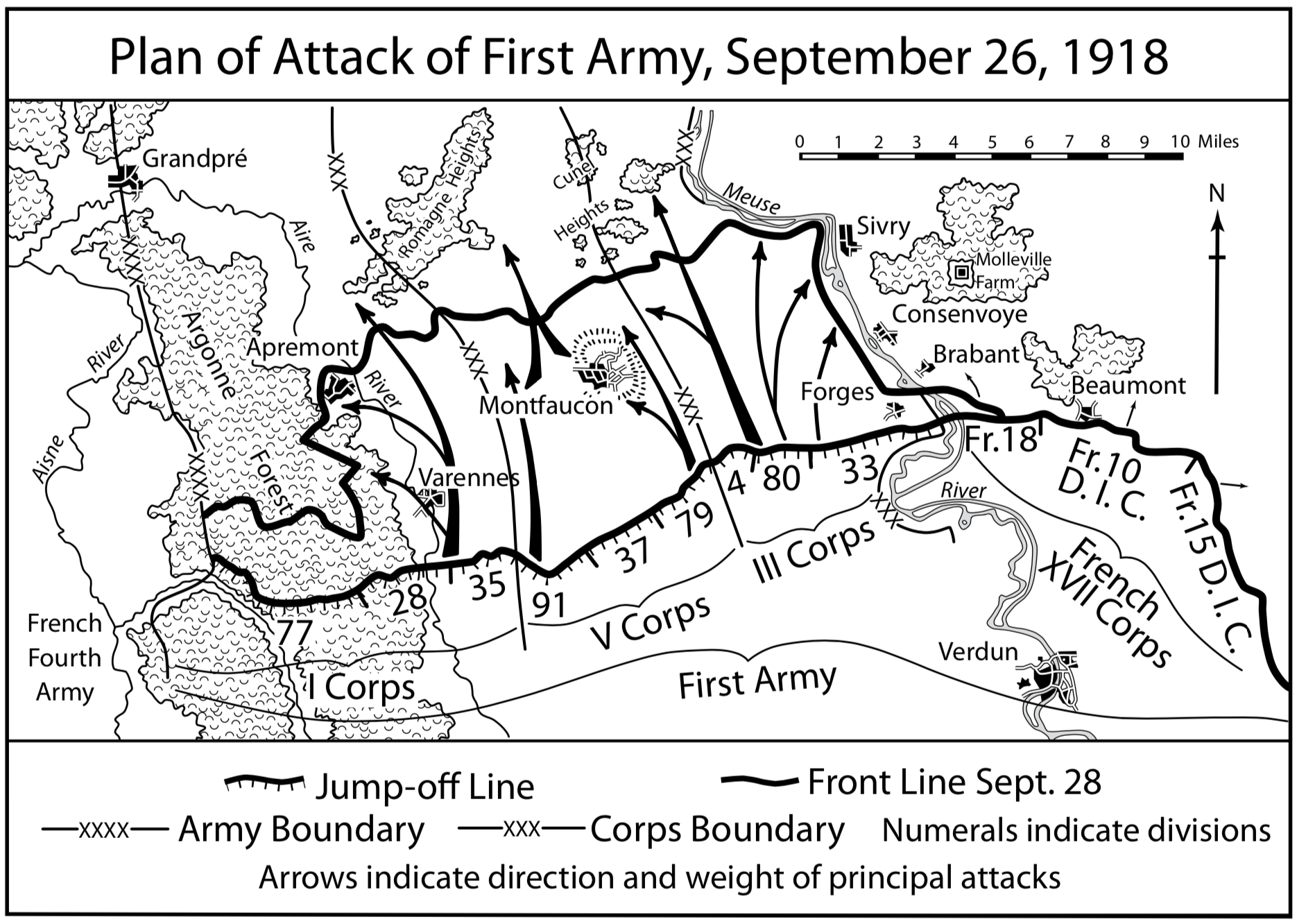

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive began on September 26th 1918 and included nine divisions across three corps of the US Army, one of the largest offensive battles of the war. Pvt Hanson in Company H, 2nd Battalion of the 308th, along with the rest of the 77th Division, were in position near the southern edge of the Argonne forest.

American Armies and Battlefields in Europe

American Armies and Battlefields in Europe

In a history of the 308th, L. Wardlaw Miles described the beginning of the barrage:

As the twilight of the 25th [of September] deepened, orders reached the 1st and 2nd Battalions to move from their rest positions in the woods which they had been holding for the last two days, to the caves along the road at La Harazee, and thence to the take-off in the trenches to the north. The woods were horribly muddy. Three machine gun men are said to have broken their legs slipping off the duck board in the darkness. Finally the troops hiked by road to the front line trenches and got placed there by 3 or 4 A.M. In the bitter cold of the morning of the 26th, they waited for the barrage which was to precede their advance. At 2.30 A.M. it began, participated in by more than 2,400 pieces of artillery along the whole American front. It is said that the actual weight of ammunition fired to clear the Argonne was greater than that used by the Union forces during the entire Civil War.

The barrage lasted for three hours, then increased to an intense preparatory bombardment for twenty-five minutes. At 5.30 the jump-off was made.

The 2nd Battalion went over the top of the trenches and began advancing in line behind the 1st Battalion. They would face little resistance, snipping barbed wire across multiple enemy trench lines. They would get lost in cold dense fog of the forest, flashes of friendly artillery shells bursting in front of them. After covering one and a quarter kilometers during the first day’s attack, the 2nd Battalion would spend the cold, rainy night dug in among the recently claimed enemy trenches.

The following few days would consist of advancing the front line a few kilometers a day at best. The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 308th were in close contact with the German army, facing periodic resistance from artillery and machine fun fire. By the 28th, the two battalions had established a headquarters on the slope of L’Homme Mort, south of Binarville near a small German cemetery. After a few days of reforming ranks and re-establishing communications with the rear, the two forward battalions of the 308th would leave their positions at L’Homme Mort on October 1st. The following morning, the 77th Division was ordered to continue their advance towards the German line.

The Lost Battalion

On their advance, the combined forces of the 308th’s 1st and 2nd Battalions, along with one company of the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry Regiment and two companies from the 306th Machine Gun Battalion, set out towards a ravine about a kilometer east of the ruins of Binarville. Companies D and F of the 308th were to remain on the west side of the ravine to provide support, while the remaining companies (A, B, C, E, G and H) were to continue down into the ravine. This force of about 550 men, many of whom were limited to one day worth of food rations for this operation, fell under the command of Major Charles W. Whittlesey.

What followed is the immortal tale of the Lost Battalion in which this group of soldiers was surrounded by German forces, fending off machine gun fire and starvation for over five days, from October 2nd to the 7th of 1918, before finally being rescued by American forces.

By best accounts, roughly 550 men would enter the ravine and be cut off in “the pocket”, a group we now call the Lost Battalion. Of that total, 101 men from Victor’s Company H, 308th were included. By the time the Lost Battalion was rescued, only 194 soldiers would walk out alive. Over 100 had been killed in that area, while another 150 were missing or had been taken prisoner by German forces.

Oddly enough, the commander of the German forces who surrounded the Lost Battalion and infamously requested their surrender, Lt Heinrich Prinz of the 76th Infantry Reserve Division (Germany army), was actually an American who had lived in Seattle for six years leading up to the war.

And Pvt Victor E Hanson, likely a Seattle area resident himself by the time he joined the war, was likely part of the Lost Battalion. As a soldier in Company H of the 308th, he would have been one of 101 men in the company who were part of the Lost Battalion during those six nights in the pocket. However, some rosters of the Lost Battalion mention a “Pvt V.E. Hanson” as a member of the 1st Battalion Headquarters, not Company H of the 2nd Battalion. Either way, it seems clear that he would have been a part of that fateful experience with the Lost Battalion.

Wounded in Battle

It was likely during those six nights in the pocket that Pvt Hanson would have been wounded in the head, either by a German bullet or maybe a piece of artillery shrapnel. Unable to be evacuated while surrounded by German forces, he would have had to suffer in pain, both from starvation as well as from a head wound. It wouldn’t be until the Lost Battalion was relieved on October 7th by the 307th Infantry Regiment that he would have been able to receive medical attention.

At that time, there were a number of dressing and aid stations in the area providing medical support to the 77th Division during their advance into the Argonnes.

The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War volume 8: Field Operations

The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War volume 8: Field Operations

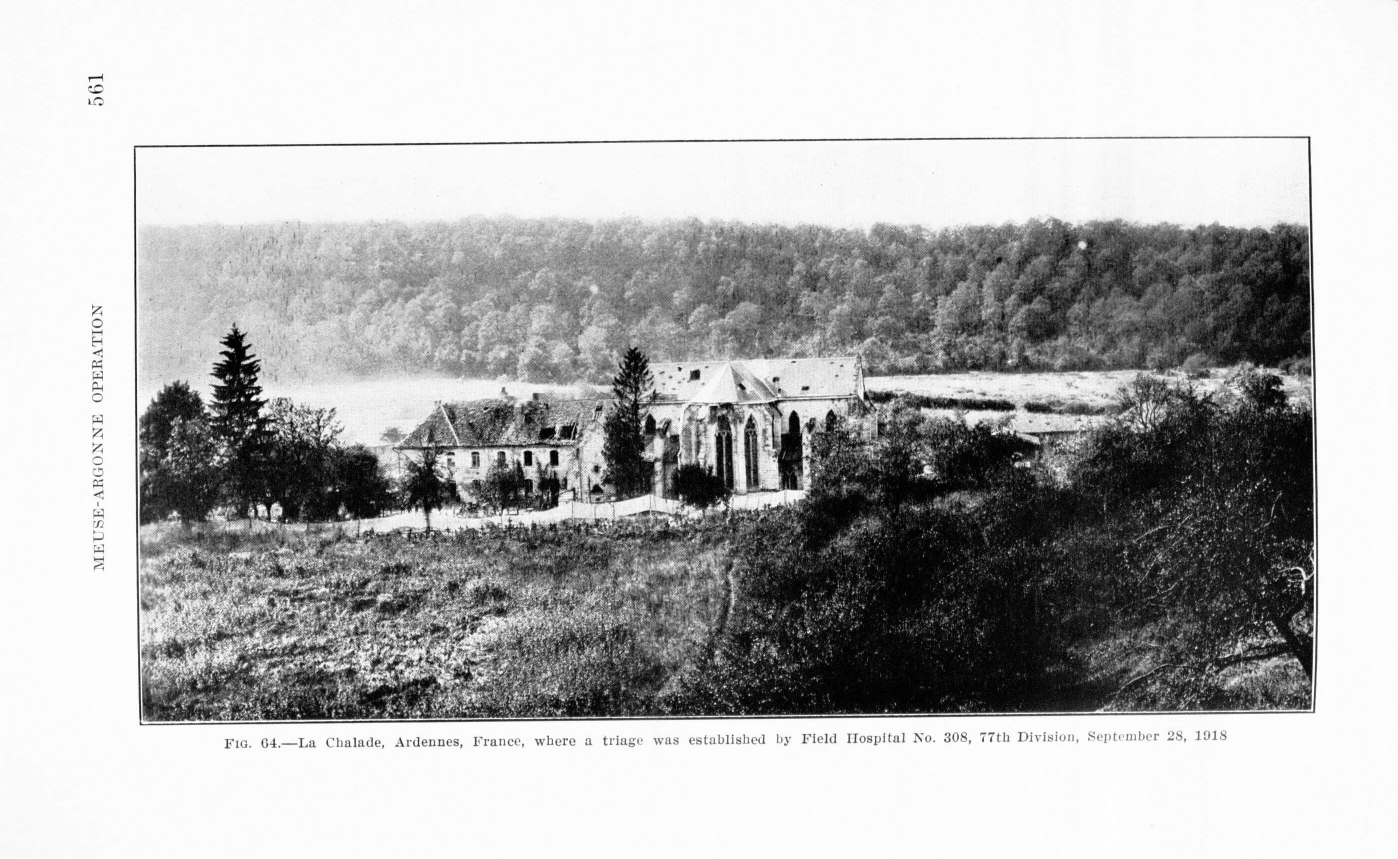

But due to the severity of his wounds, Victor probably would have been transported south to the nearest field hospital (No 308) at La Chalade.

The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War volume 8: Field Operations

The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War volume 8: Field Operations

It was likely here, on October 12th 1918, that Pvt Victor E Hanson would fatally succumb to his wounds. After only three and a half months since joining the US Army at Camp Lewis, Washington, Victor would be dead in France.

Almost a month later, on November 11th 1918, the armistice between the Allies and Germany was signed. The Great War in Europe was over.

Death’s Notice

Victor’s death was reported in the Seattle newspaper two months later in late December 2018. His last name and middle initial are misspelled, but his father Hans Hanson is listed as next of kin in Bellevue. Victor joined the almost 200,000 American soldiers dead, wounded or missing by the end of the war, including almost 1,800 men from the state of Washington.

The Seattle Star, December 28th 1918

The Seattle Star, December 28th 1918

A few days later on January 2nd 1919, Victor’s hometown newspaper in Princeton, New Jersey would also publish notice of his death.

The Princeton Union, January 2nd 1919

The Princeton Union, January 2nd 1919

By this time, Victor’s parents and two of his sisters, Bertha and Agnes, were all living in Bellevue, Washington. His older brother Arvid was nearby at Camp Lewis, presumably still in the army and yet to be discharged. Another brother George, previously of Condon, Oregon, was now in Malone, Washington just southwest of Seattle. His oldest sister Hannah was living in Oregon City, Oregon while his oldest brother William was the only Hanson sibling still residing back in Minnesota.

A Hopeful Search

More than year after his death, a strange notice was posted in newspapers throughout the country. The American Red Cross began to ask for the public’s aid in locating the possibly still-alive Victor Edgar Hanson. Apparently, he had been last spotted in the port city of Brest, France as late as February 1919, roughly four months since he had reportedly died from his wounds near the Argonnes. However, due to the head wound he had received, it was presumed he might have no memory of hs name or past.

The York Daily Record, December 19 1919

The York Daily Record, December 19 1919

A month later, the American Red Cross would emphasize that Victor’s relatives were driving the search for Victor, but they “had been unable to secure any proof of his death and have exhausted the usual means of inquiry”. They even believed that he may have returned to the States but was possibly still at a hospital due to his amnesiac condition.

The Daily News and the Times (Neenah, Wisconsin), January 13th 1920

The Daily News and the Times (Neenah, Wisconsin), January 13th 1920

It is curious that someone, presumably in the Army, believed they had recognized Victor in Brest and were able to inform his parents. While it’s possible that he may have been in Brest at that time (if he were returning to the States as a casualty), it’s not clear who would have recognized him. It most likely would have been one of his fellow soldiers in the 308th Infantry, but the regiment wouldn’t arrive in Brest until two months later in mid-April 1919 on their way back home to New York.

While it’s tragic to think of Victor’s family searching for a son they believed to be still alive, in all likelihood Victor had actually succumbed to his wounds during the early days of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, especially considering the heavy losses that the 308th sustained during their advance into that forest.

The Loss of Parents

Less than four years after their son’s death, both of Victor’s parents would also be dead. His father Hans passed away on June 13th 1922 and, only two months later, his mother Christina passed away on August 14th after a series of medical complications the preceding years. The Hanson couple would be survived by their six remaining children living in Oregon, Washington and Minnesota.

The uncertainty they must have felt about the loss of Victor likely weighed on them heavily in their final years. Hans and Christina would be survived by their six remaining children, likely surrounded by the four who lived near them in Bellevue at the time of their passing.

Buried in France

Sadly, their son Victor Edgar Hanson never returned home from France after the war. His body would eventually be buried at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery near the village of Romagne-sous-Montfaucon in northeastern France.

Visiting Vintage/Robert Shay

Visiting Vintage/Robert Shay

He rests at peace in Grave 2, Row 1 of Plot A, one of over 14,000 fellow soldiers who paid the supreme sacrifice during the Great War.

L.C. McCollum, History and Rhymes of the Lost Battalion

L.C. McCollum, History and Rhymes of the Lost Battalion

Further Reading

More on The Lost Battalion

- The Operation of the So-Called “Lost Battalion”, October 2 to 8, 1918.

- History and Rhymes of the Lost Battalion, by L.C. McCollum

- Was There Such a Thing in the World’s Great War as The Lost Battalion, by Walter J. Baldwin

More on the 308th Infantry Regiment

- History of the 308th Infantry, 1917-1919, by L. Wardlaw Miles

- Our Company, by John Wesley Adams and L.C. McCollum; Company A, 308th Infantry

- Let’s go! The story of A.S. no. 2448602, by Louis Felix Ranlett; Company B, 308th Infantry

- History of Company D, 308th U.S. Infantry, 77th Division, AEF, by

- The History of Company E, 308th Infantry, 1917-1919, by Corp. Alexandar T. Hussey and Pvt. Raymond M. Flynn; Company E, 308th Infantry

- World War I Army Diary of Private Irving Greenwald; Company E, 308th Infantry

- The Journey: An American Soldier in World War I, by D. Kent Decker; Company E, 308th Infantry

More on the 77th Division

- History of the Seventy Seventh Division

- *The Victorious 77th Division (New York’s Own) in the Argonne Fight, by Arthur McKeogh

- Posted on:

- December 27, 2019

- Length:

- 16 minute read, 3406 words

- See Also: