Clarence Johnson

A dairy truck driver who became "one of the best line men in Company L", killed in the beginning of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive at Miller Hill in the fall of 1918.

Born in Sioux City

The son of Scandanavian immigrant parents, Clarence Oscar Johnson was born in Sioux City, Iowa on January 3rd 1896.

His father Charles John Johnson was born in Sweden in December 1866 and moved to America in 1886. His mother Lena was born in Norway in December 1862 and moved to the states in 1889, three afters Charles. They married around 1893, at the somewhat late ages of 27 and 31 respectively. At some point after moving to America, the Johnson’s would settle in Sioux City, Iowa where Clarence’s father would find work at an electrical plant.

Their first son Abner was born only a year later in April 1894, followed by the birth of Clarence less than two years later on January 3rd 1896. A daughter Mabel would follow in 1897 and a third son Robert in 1899.

A Move to Seattle

In early 1903, when Clarence was 7 years old, the Johnson family would pack up and head west, moving from Sioux City, Iowa to Seattle, Washington. They would settle into a house at 1318 21st Ave South, southeast of downtown Seattle. By 1910, Clarence’s father Charles would be employed as an electrical contractor.

The Draft

By 1917, Clarence was 21 years old and working as a truck driver for the Turner & Pease Co, a large butter manufacturer in the state.

In April of that year, the United States would declare war on Germany and officially enter World War I. A few months later, Clarence would register for the first military draft on June 5th 1917.

He would unsuccessfully claim an exception from the draft due a “physical condition”, but a few months later, on September 4th 1917, Pvt Clarence O. Johnson would be enlisted in the US Army.

It was probably only few days or maybe weeks later that Pvt Johnson would head south to Camp Lewis and join the newly formed 91st Division.

91st Division

91st Division, National Army, Camp Lewis (1917)

91st Division, National Army, Camp Lewis (1917)

Officially organized on September 6th 1917, the 91st “Wild West” Division comprised military-age men from the eight western states of California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming and the territory of Alaska. Having enlisted in early September, it’s likely that he would have been part of the first group of men to arrive at Camp Lewis, one of almost 400 other men to be the first to arrive from the state of Washington.

91st Division, National Army, Camp Lewis (1917)

91st Division, National Army, Camp Lewis (1917)

The 91st was built up of four infantry regiments, the 361st, 362nd, 363rd and 364th Infantry Regiments. The 361st/362nd, along with the 347th Machine Gun Battalion, made up the 181st Infantry Brigade while the 363rd/364th and the 348th Machine Gun Battalion made up the 182nd Infantry Brigade. Additional units included field artillery, medical detachments, engineers and other support troops that made up a division.

361st Infantry Regiment

The 361st Infantry Regiment specifically was made up mostly of men from the states of Oregon and Washington. Pvt Johnson would join this regiment as a rifleman in Company L, 3rd Battalion of the 361st.

Pvt Johnson and the rest of the 361st Infantry would spend the following nine months at Camp Lewis undergoing military training to learn infantry basics, including marching, marksmanship and maneuvering. On June 22nd 1918, the 361st Infantry and the rest of the 91st Division would finally leave Camp Lewis to head to the war in Europe.

Leaving for France

Pvt Johnson and Company L boarded the last train in a convoy of eight that would load up the 361st Infantry Regiment and head east across the United States destined for Camp Merritt in New Jersey. Along the way, his train made a brief stop in Minnesota, allowing the men of Company L to bath in a nearby river paved with clam shells. After six days of travel, the regiment arrived in New Jersey and marched to Camp Merritt.

After a week of physical assessments and equipping at the camp, Pvt Johnson and over 2,400 men would board the SS Scotian, a British transport ship, in the port of Hoboken.

He would be boarding the ship with the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 361st Infantry Regiment, as well as a small contingent from their brigade headquarters and almost 500 men from two different base hospitals. On July 6th 1918, the Scotian set sail from New York harbor to head across the Atlantic.

For the 11-day trip across the ocean, the men of 361st had little to eat except goat, ham and an apparently inexhaustible supply of fruit preserves, for which the men gave their ship the nickname “The Good Ship Marmalade”.

On the evening of July 17th, the Scotian dropped anchor in the port of Glasgow, Scotland. The 361st had arrived in Europe.

An Arrival and More Training

The 361st would then make their way to Southampton, England and then across the channel to Le Havre, arriving in France on July 20th. The regiment would then spend the next two days crossing the country by train, ending up in the Montigny-Le-Roi region of northeastern France. Pvt Johnson and the rest of the 3rd Battalion would settle into the nearby town of Sarrey, spending the next six weeks undergoing more training of practical battlefield skills, including the use of automatic rifles and bayonets, as well as gas defense, rifle practice and visual signaling. It was here that Major Oscar F. Miller would take command of the 361st’s 3rd Battalion, which included Pvt Johnson and Company L.

By early September, the 361st were ready to head to the front of the war, first setting off south in a march to Chalindrey before boarding trains heading north to Demange-Aux-Eaux. It was here that the 361st first felt how close they were to the front, seeing enemy and allied planes overhead and hearing the faint sounds of gunfire in the distance. The following week, the 361st and the rest of the 91st Division would be held in reserve during the St Mihiel offensive.

They would spend the next week and a half continuing north, through Void-Vacon, Marats-La-Grande, Nubécourt and Bois-Le-Comte. They were now marching closer and closer to the front, either under the cover of darkness at night or carefully under cover during the day, part of the “Silent Approach of the Great American Army” that was positioning itself for the next large-scale offensive of the Allies against the German army.

The 361st would continue their march closer and closer, first to Parois then Fontaine-Au-Chene Ferme where they would pitch their tents under tree cover, only 3.5 kilometers from the German lines. The 361st, as well as the rest of the 91st Division and the US First Army at large, were increasingly crowding into this rural part of France.

It was possibly during this time that Pvt Johnson would be promoted to the rank of Corporal, indicating that he had become either a squad or team leader in his company.

Preparations

On September 25th, the 361st received their orders for the upcoming offensive push and the regiment organized itself accordingly. The 3rd Battalion, led by Major Miller, would be leading the way in the front, supported by a machine gun battalion. Cpl Johnson’s Company L, led by Captain William J Potter, took its place on the left and Company M took the right. Company I and Company M would provide support from behind.

The 361st and the 91st Division were positioned in the center of the 30 kilometer front of the American Army’s mass of readied troops. That evening, at 11:30pm, supporting artillery began to shell the German defensive positions in preparation for the upcoming US offensive. Arthur Ruhl, writing for Colliers’ Weekly after the war, would describe his experience of the artillery flying overhead, likely similar to what Cpl Johnson himself would have experienced:

“Batteries, massed in the dropping haze, were banging away all about us–‘seventy-fives’ that suddently whack the air with dry, sharp reports, now singly, now tumbling viciously over each other; ‘heavies’ that seemed to split earth and sky when they unexpectedly crashed from the near-by darkness; or, father off, flung down the countryside a long thunderous resonance across the harp of the woods. The whole sky flicked from horizon to horizon as if in the flares from hundreds of blast furnaces. And over our heads, now with quick, pert, almost frivolous whistle,; now with long-drawn, lazy moans; and now with a rushing sound of a departing express train, the shells began racing over into the enemy’s lines. Near-by batteries, firing salvos, slapped the ears with sharp, physical concussions. There would be instants of pause sometimes, and then scores of detonations crowding over each other in a curious sort of localized thunder that reminded one of torrents of great balls rolling downstairs.”

Throughout the night, the troops continued to push themselves for the upcoming offensive. By 4:30am the following morning on September 26th, the 361st had taken up positions along the Varennes-En-Argonne / Avocourt road.

One hour later, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive would begin.

The Jump-Off

At 5:30am on September 26th, the 361st jumped off and went over the top of their trenches to begin advancing on the German troops in the Argonnes forest. In their early march, they met little resistance, mostly finding just the effects of the recent artillery, including destroyed German defensive structures, new holes that were five to fifteen feet deep and ten to thirty or more feet wide, as well as thermite still burning on the ground or on tree stumps.

The 361st would advance north, overcoming scattered machine gun nests, taking German prisoners and clearing German trenches. By the end of the day, the 361st had taken up position just south of the town of Epinonville. The following day would find them maneuvering to envelope the town and take up increasingly forward positions while meeting stiff resistance from the German army.

The next day, September 28th, the 361st would move to take Epinonville, and the nearby town of Eclisfontaine, only to find them relatively undefended as the German army had withdrawn in the night. They would continue on to a pair of woods just north, known as Les Epinettes Bois and Bois de Cierges. Gathering up their men on the edge of the woods, they prepared to advance across an open farm field towards their next objective, the town of Genges. German machine guns and artillery were sweeping the field, and firing into the woods where the troops were gathering. Casualties among officers and enlisted began to rapidly increase, including Cpl Johnson’s commander of Company L, Captain Potter, who was wounded by a machine gun bullet.

It was here that the 3rd battalion commander, Major Oscar F. Miller, would gather his troops to mount an attack to push across the nearly one thousand yards of the open field. In the middle of the field stood a steep ridgeline nearly 300-400 yards long, a small objective that would later to become known as Miller Hill.

Miller Hill

The 3rd Battalion, including Cpl Johnson and Company L, was led by Major Miller in the front and pushed out of the woods to take the field, with soldiers firing from the hip as they advanced. They were immediately met by a concentration of machine gun and artillery, which wounded Major Miller in the arm and leg. He urged the 3rd Battalion on to continue the attack, in which they swept down into a deep gulch just in front of the ridge line that would come to bear his name. They then crossed a shallow dip and crested the hill where the wounded Major Miller was hit in the stomach by what would prove to be a fatal bullet. Falling to the ground, he waved the battalion to continue on, shouting “Never mind me, take the ridge.”

Killed in Action

It was here on Miller Hill that Cpl Clarence Oscar Johnson would meet his fate. The charge on Miller Hill would lead to many casualties by enemy machine gun and artillery, including the fatal wounding of his 3rd Battalion’s commanding officer, Major Miller.

The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 6th 1919

The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 6th 1919

But the charge would also lead to many other casualties in the 3rd Battalion, including Company L. During the charge, Cpl Johnson was grouped together with a handful of other men from his company when an artillery shell landed amongst the group, killing Cpl Johnson instantly. The story of his death would later be told by Prof. Colin V. Dyment, a journalist with the American Red Cross who was embedded with the 91st Division at the time.

The Spokesman Review (Spokane, WA), April 30th 1919

The Spokesman Review (Spokane, WA), April 30th 1919

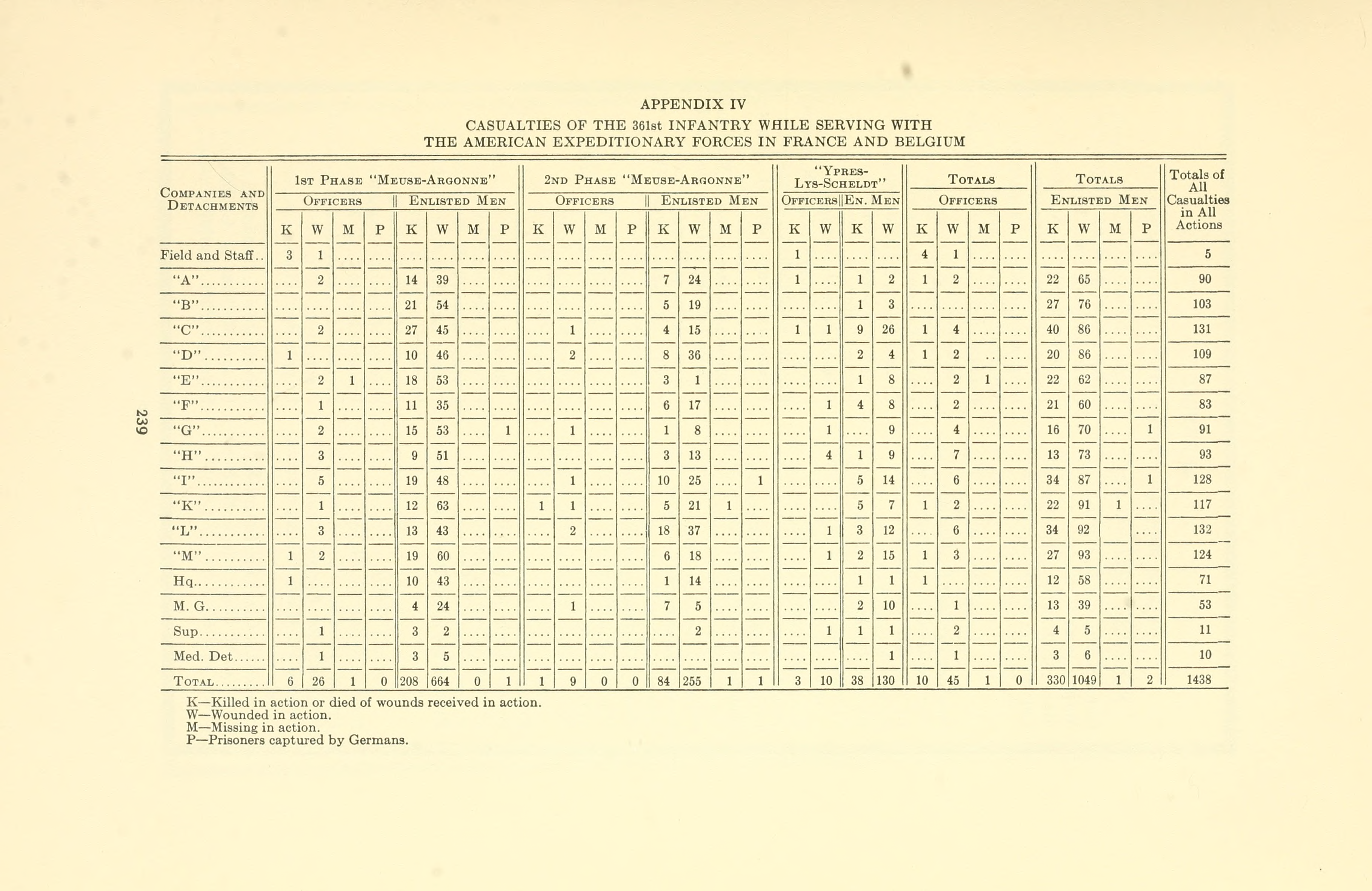

Cpl Johnson was one of thirteen other enlisted men in Company L killed during this first phase of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, with another forty-six men wounded.

600 Days' Service: A History of the 361st Infantry Regiment of the United States Army

600 Days' Service: A History of the 361st Infantry Regiment of the United States Army

While Company L had an original muster roll of 238 men when they organized at Camp Lewis, by the end of the war 34 of those men would be dead and another 93 would be wounded.

600 Days' Service: A History of the 361st Infantry Regiment of the United States Army

600 Days' Service: A History of the 361st Infantry Regiment of the United States Army

A year after joining the US Army, and a little over two months since arriving in Europe, Clarence Johnson’s war would be over.

The fight for the Meuse-Argonne would continue for another forty some days before the signing of the armistice on November 11th 1918, marking the end of the Great War.

Burial

After the war, Clarence’s body would eventually be buried at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery near the village of Romagne-sous-Montfaucon in northeastern France.

Find A Grave

Find A Grave

Clarence Oscar Johnson rests at peace in Grave 23, Row 35 of Plot E, one of over 14,000 fellow soldiers who paid the supreme sacrifice during the Great War.

Further Reading

More on the 361st Infantry Regiment

- The 361st Infantry Regiment, 1917-1955

- 600 days’ service; a history of the 361st infantry regiment of the United States Army

More on the 91st Division

- The Story of the 91st Division

- The Ninety-First, the First at Camp Lewis

- 91st Division National Army Camp Lewis

- The 91st Infantry In World War I: Analysis of an AEF Division’s Efforts to Achieve Battlefield Success

- Posted on:

- December 27, 2019

- Length:

- 12 minute read, 2406 words

- See Also: