Arnold Odenweller

Arnold L. Odenweller was born on June 8th 1895 in Putnam County, Ohio, one of ten children born to Edward L. Odenweller and Margaret Odenweller (nee Hempfling).

The Draft

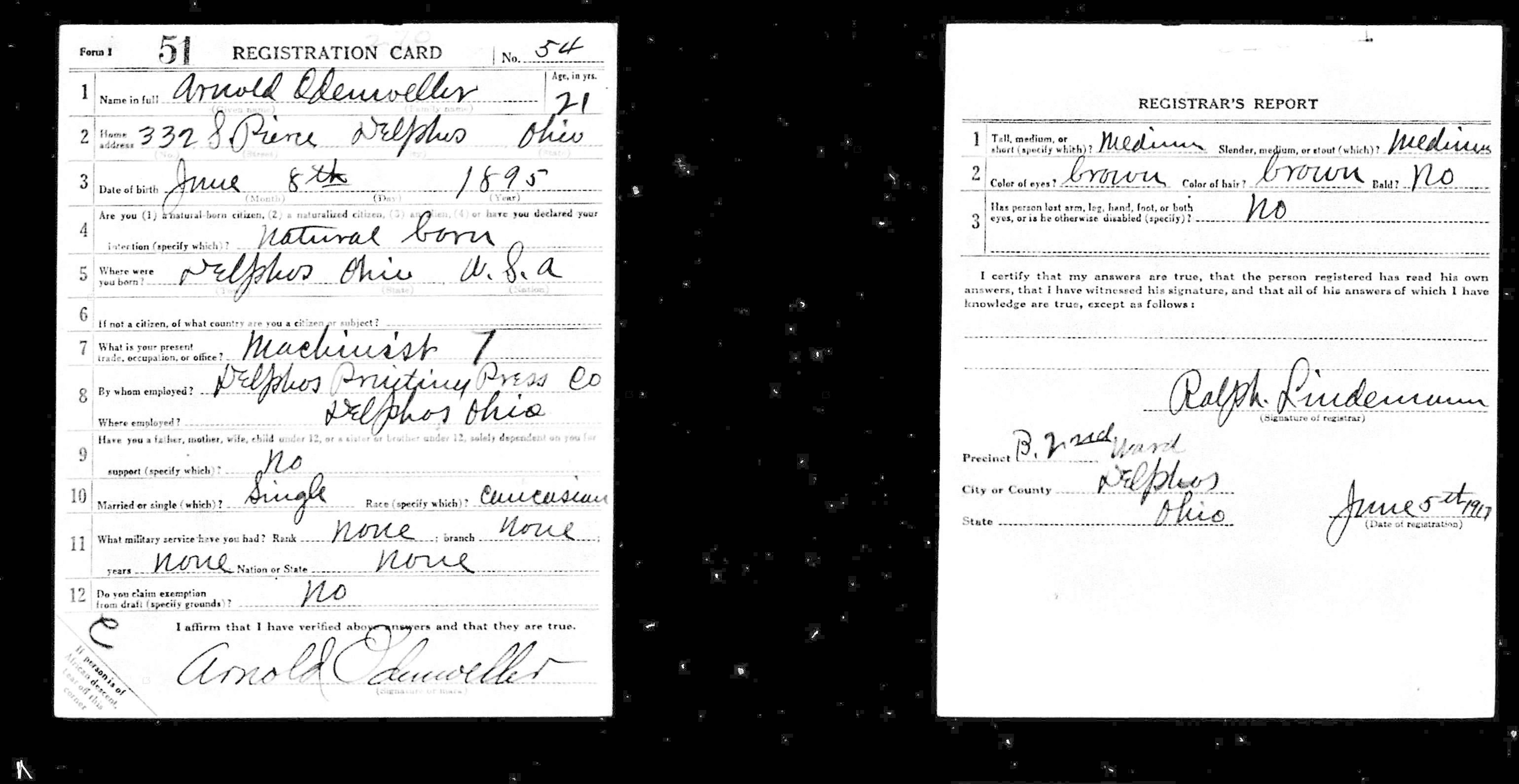

On June 15th 1917, only 3 days before his 22nd birthday, Arnold registered for the US draft, the first of World War I.

U.S. Selective Service Registration Card, 1917

U.S. Selective Service Registration Card, 1917

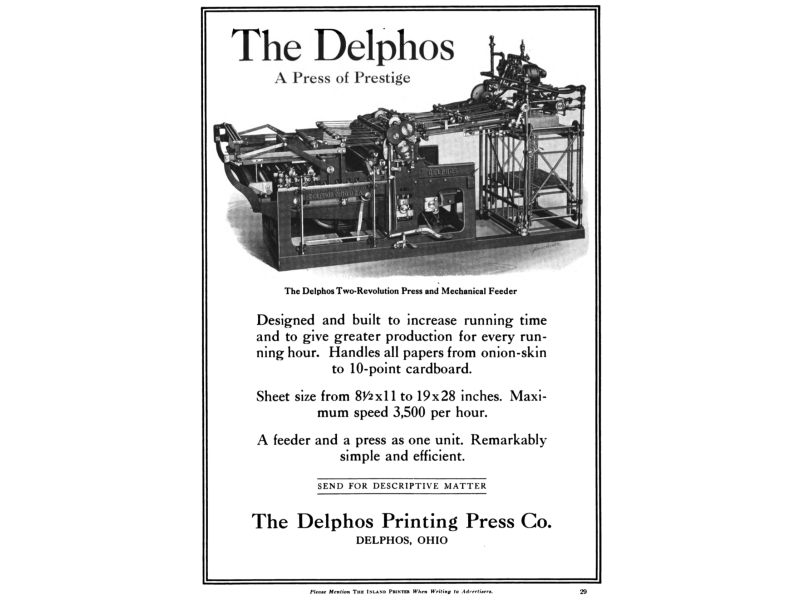

At the time of his registration, he was a machinist at the Delphos Printing Press Company, likely working on their flagship printing press, The Delphos.

The Inland Printer, Volume 57, April 1916 to September 1916

The Inland Printer, Volume 57, April 1916 to September 1916

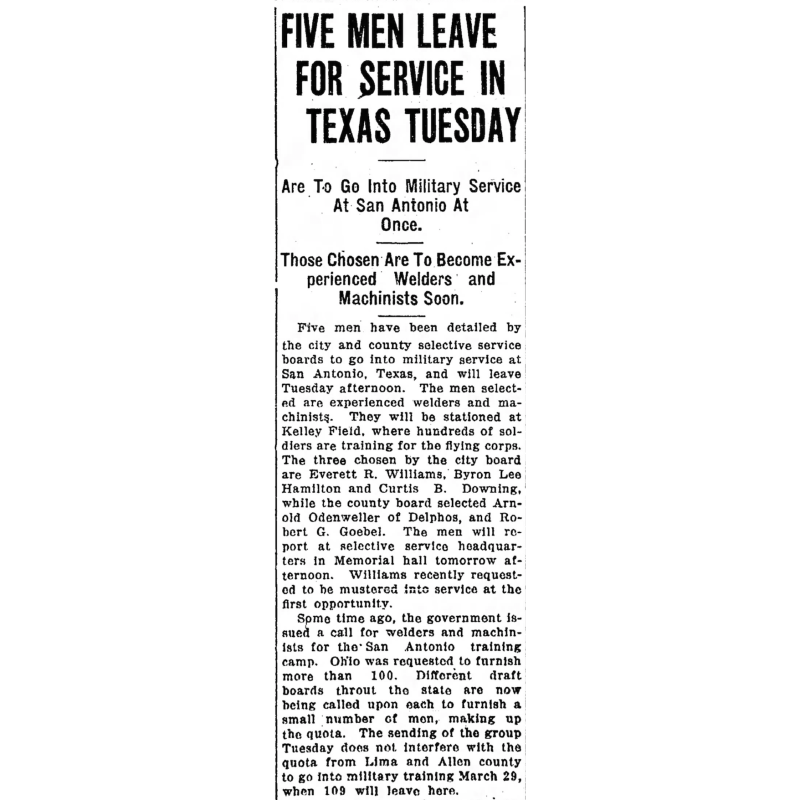

About nine months after registering for the draft, Arnold was one of five local men (all experienced welders and machinists) selected by the city and county draft boards, called to duty in the US Army Air Service. They would be sent from Ohio to Kelley Field in San Antonio, Texas, a new airfield which had been built just a year earlier to begin training men in the new flying corps.

The Lima News, March 17th 1918

The Lima News, March 17th 1918

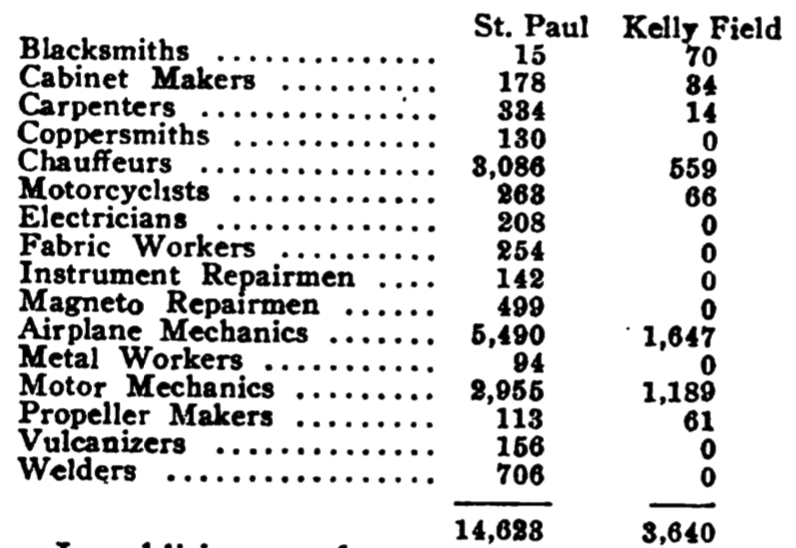

It’s unclear if Arnold ever made it to Texas however. Around the time he entered the Air Service, it only had two Mechanics Schools: one in St Paul, Minnesota and the other at Kelly Field in Texas. These schools trained over 17,000 men in all manners of mechanical skills related to airplanes.

National Service with the International Military Digest, January 1919 Vol 5 No 1

National Service with the International Military Digest, January 1919 Vol 5 No 1

It’s possible that Arnold didn’t even leave the state of Ohio when he first received his orders to report to the US Army’s Air Service. Instead he likely headed to Wilbur Wright Field in Fairfield, Ohio to join the Aviation Armorers School, a school that had recently transferred from Kelley Field.

Armorers School

In January 1918, Colonel Alfred H. Hobley was assigned as commanding officer of a new Armorers School at nearby Ellington Field in Houston, having previously been at Kelley Field. Less than two months later in March 1918, the school would move to Wilbur Wright Field in Ohio. This move helped the Armorers School incorporate more research work into their training, due to its proximity to McCook Field where aerial research, experiments and tests were being done on new gunnery, bombing and sighting techniques.

Thus the Armorer’s School could incorporate the most advanced aviation techniques into their course work:

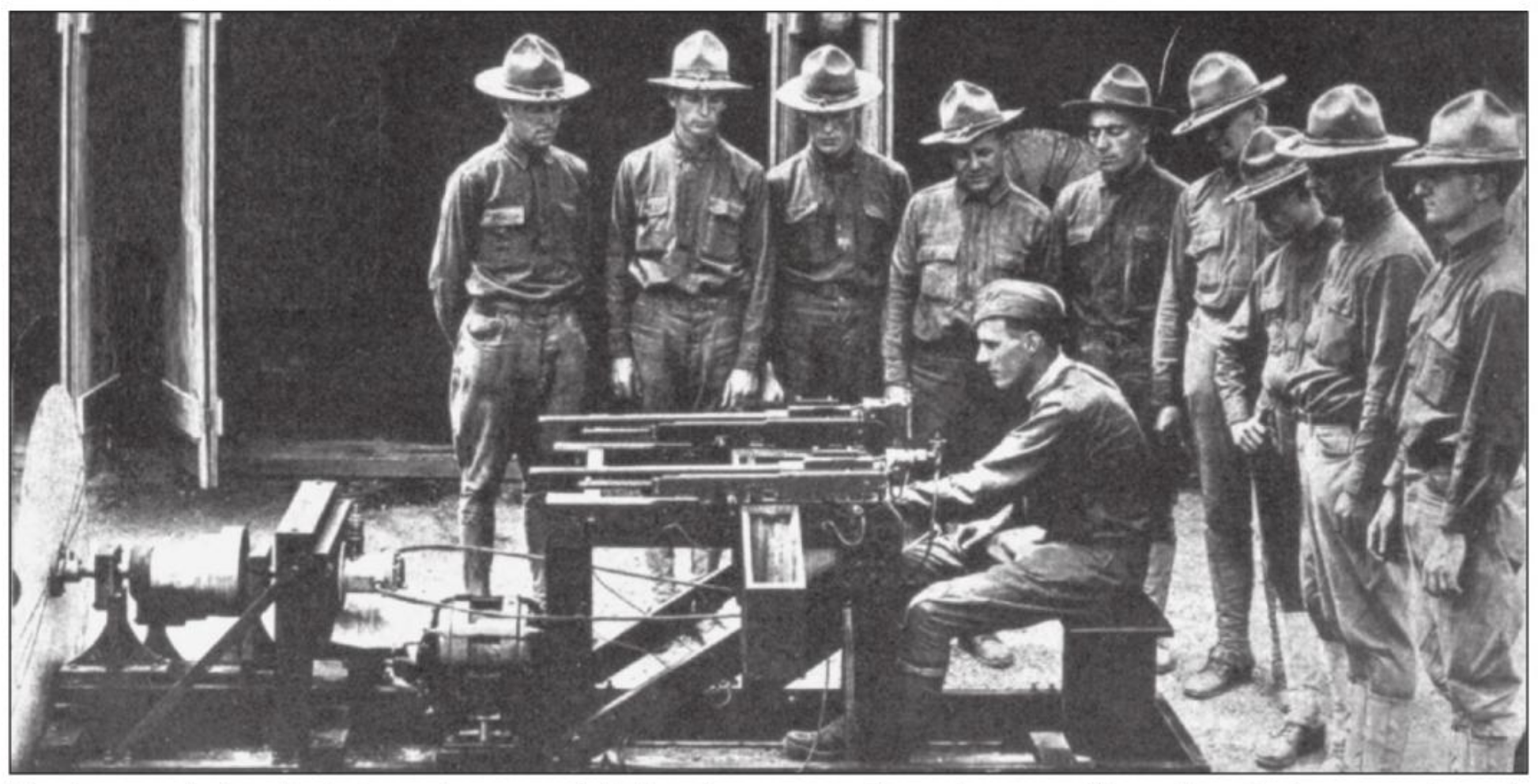

Students of the Aviation Armorers' School are seen learning to adjust the timing on aircraft machine guns in this photograph taken in 1918. The school had two functions: one, to test all machine guns issued to the aviation section, and two, training new armament officers and their enlisted assistants. The six-week course trained armorers in the operation of machine guns, their sights and synchronization mechanisms, and the storage and mounting of bombs.

Dayton Aviation: The Wright Brothers to McCook Field by Kenneth M. Keisel

Dayton Aviation: The Wright Brothers to McCook Field by Kenneth M. Keisel

Dayton Aviation: The Wright Brothers to McCook Field by Kenneth M. Keisel

Additionally, a look at some letters from fellow armorer’s offer a glimpse into what Arnold’s day-to-day would have been like at Wilbur Wright Field.

Paul B. Phillips of San Bernardino, California, having previously been at Kelley Field, wrote home to his parents soon after transferring to Wilbur Wright Field and described the new landscape:

The flying field proper is a great level floor surrounded by rolling hills. Around the northern edge is a long string of hangars, and above the hangars, on the hills, are the barracks, warehouses, headquarters buildings, etc. From our quarters we look out across the flying field to the hills opposite, which are covered with woods. To the rear and on both hands extend well cultivated farms---we even hear a rooster crow once in a while. The landscape is dotted with silos.

The San Bernardino County Sun, May 8th 1918

Paul went on to describe a day in the life of his military service to his parents, particularly noting the food, strict regulations and cleanliness requirements of his new life. He described waking up 5:45 am for dress and washing, followed by formation and breakfast. After eating, they would police the barracks and make their beds, followed by drill and calisthenics from 7:20a to 8am. From from 8am to noon, the armorer would be in school studying their craft, with an hour break at lunch followed by more schooling until 5pm. After some time off, they’d eat supper at 6pm followed by liberty (which mostly involved more studying), with lights out at 9:30pm.

Of his studies, Paul clarified a previous mistake with his parents:

But I haven't told you what I am studying. I said before that I was in the First Armored Car Detachment. That was a mistake; it is Armorer's Detachment. The position of armorer is a new one created by the increased use of battle plans. Every airplane is armored with four machine guns and with bombs of sundry types and uses. To be able to mount, repair, and care for these guns, and to handle high explosive bombs, requires very specialized training. That is what we are getting.

The San Bernardino County Sun, May 8th 1918

And he went on to describe the delicate nature of their work with machine guns:

I had heard of machine guns before and seen their pictures, but I never realized their complexity until I saw one in pieces scattered on a workbench. The first time you put one together you are liable, like the boy with the watch, to have quite a collection of springs and odd-looking objects left over. To realize the accuracy with which these guns must be assembled, and the delicacy of the apparatus which controls their fire, you only have to know the mode of their operation. The Marlin gun, which I am studying now, fires 650 times a minute. That is considerably faster than you can think, but the remarkable part of it is that these shots are fired through a propeller, which is revolving 1,400 times a minute, without striking the blades. You can see that the slightest variation from absolute accuracy would be disastrous. The timing apparatus is a wonderful mechanism.

The San Bernardino County Sun, May 8th 1918

The “wonderful mechanism” described by Paul B. Phillips was likely in reference to the Colley-Constantinescu Gear, or “C.C. Gear”. The C.C. Gear is what’s known as a “synchronization gear”, a key piece of technology (invented only a year prior in 1917 by George Constantinescu and Major G.C. Colley) which prevented machine guns from firing into the spinning airplane propellers in front of them.

The importance of this mechanism was also highlighted by Lindsay Amoss, another armorer in training and native of Windsor, Colorado, in a letter home:

One more week and school will be over, and several hundred of us will have a fair knowledge of machine guns, bombs, ring sights and C.C. Gears. If you don't know what ring sights and C.C. Gears are, ask Mac Dillon, and if he don't know now, he will, before he gets thru his fighting school.

The Windsor Beacon, June 6th 1918

An armorer’s training required mastery of both Allied and enemy weapons, requiring proficiency in handling and repair of machine guns in particular. In a letter home to his mother, Field Brundidge of Fort Scott, Kansas emphasized a particularly key skill that armorers trained on:

We may go out at night when needed to repair the guns on the planes, and because of that we must be able to put the entire gun together blind-folded and there are about two hundred parts. Just as soon as the planes comes in we rush out, get the gun and bombs he has left, and repair them. We have three machine guns to learn, and also six bombs. We had tests yesterday on taking apart and assembling the Vickers machine gun and I did it in two minutes, only one fellow beat me seven seconds.

Fort Scott Daily Tribune-Monitor, May 2nd 1918

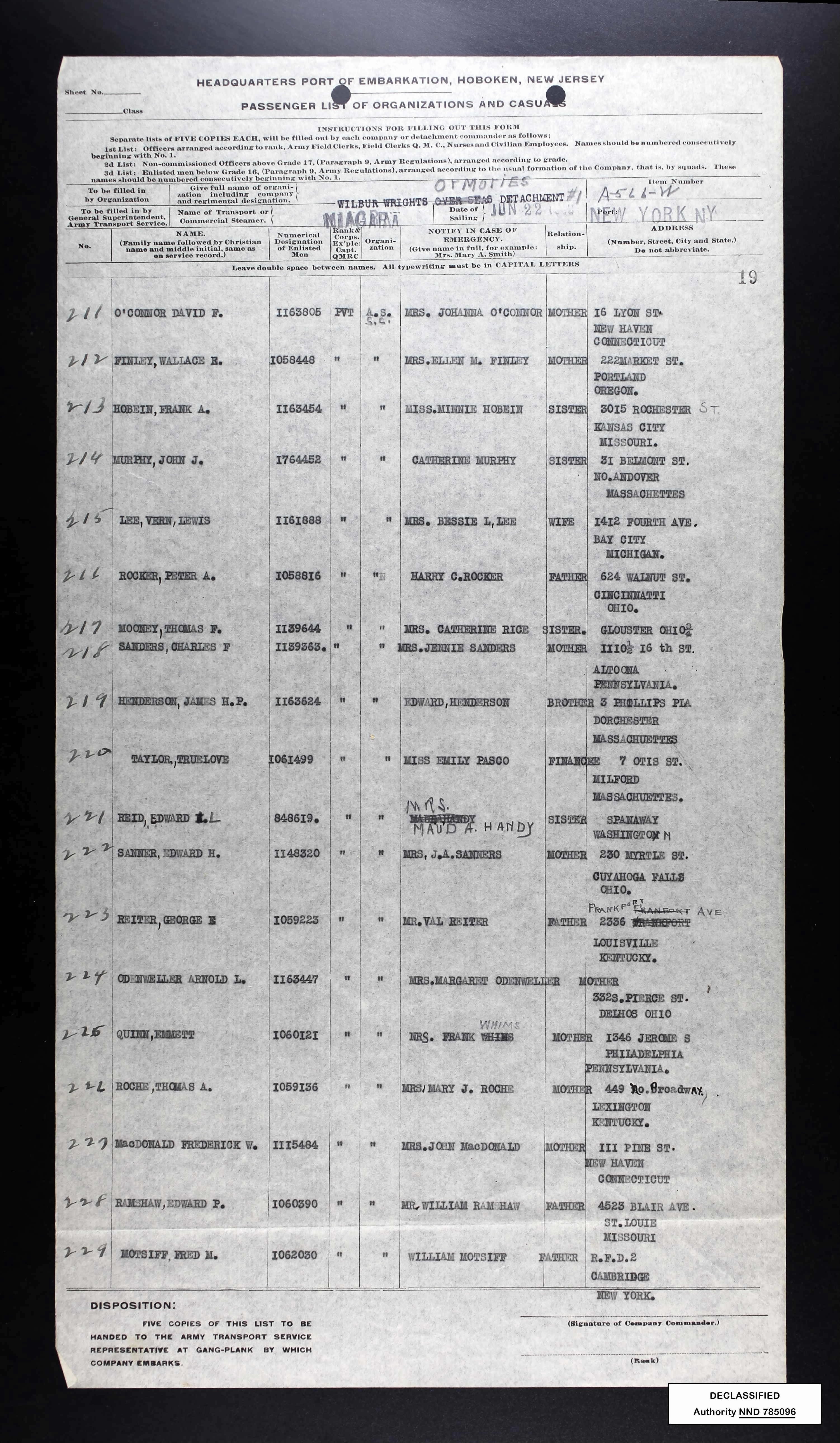

Finally, fellow armorer Walter H. Norcross of Medford, Oregon wrote home for Mother’s Day to give his mother an update on his life at Wilbur Wright Field, including the dangers of his work and his aspirations:

Medford Mail Tribune, May 27th 1918

Medford Mail Tribune, May 27th 1918

And with that, after a six-week course, the newly graduated students of the Aviation Armorer’s school would set sail for Europe.

Off to the War

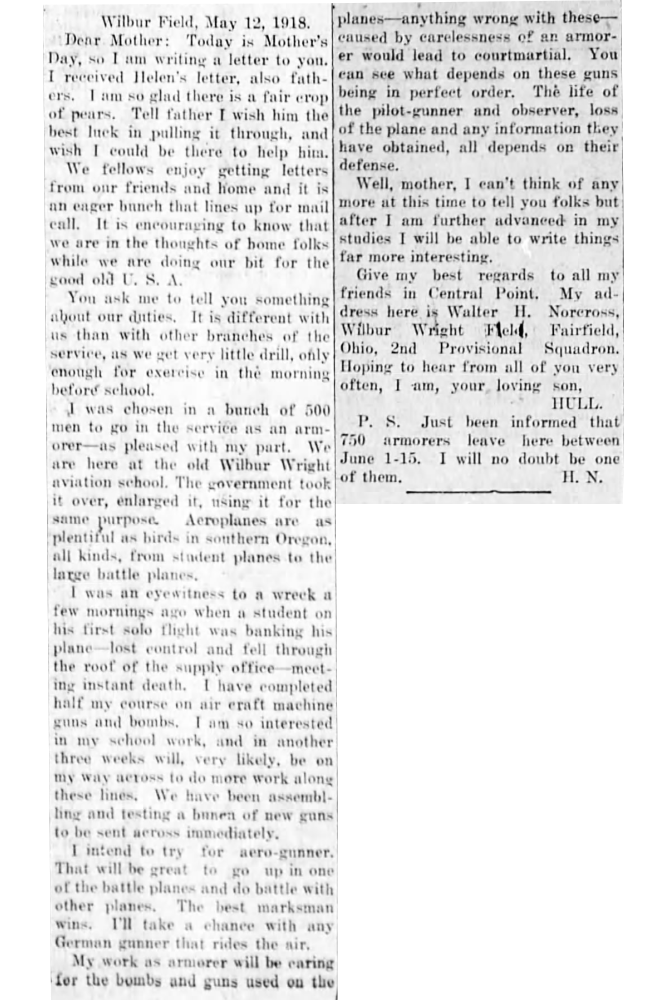

Arnold would join one of two new armorer groups, “Wilbur Wright’s Over-Seas Detachment #1”, leaving Wilbur Wright Field and traveling by train from Ohio to New York City. After their arrival, over 500 men, including the two armorer groups, would start to board a ship at 9 in the morning, finishing just before noon. A few hours later, the transport ship Niagara would push off from Pier #57 at 1:25pm on June 22nd 1918, setting sail for France.

Headquarters, Port of Embarkation, New Jersey, June 22nd 1918

Headquarters, Port of Embarkation, New Jersey, June 22nd 1918

Notably, a young aviation pioneer Alfred V. Verville also traveled onboard the Niagara. As an aircraft designer based at McCook Field (the research facility near Wilbur Wright Field), Verville was sent abroad by the Directory of the Bureau of Aircraft Production. He was assigned a special mission to study the Allied pursuit plane program and its design, specifically the French and British planes that were more advanced than those being built in the United States at the time.

Arnold and the rest of the armorers in Wilbur Wrights Over-Seas Detachment #1 would land in Brest, France a few weeks later after their journey across the Atlantic Ocean. Upon arriving in France, armorers in both detachments were likely transferred to the handful of various Aero Replacement Squadrons across France. These replacement squadrons supplied new troops to all of the American aero squadrons operating in France.

It was likely soon after arriving in France that Arnold would be transferred through a replacement squadron and then on to join the 1st Aero Squadron.

1st Aero Squadron

The 1st Aero Squadron, to date, is the oldest operating military aviation unit in the world. Originally formed in 1913, it would first see service during the Mexican Border War. The squadron would go on to deploy to Europe in the fall of 1917 to serve in WWI, and would become the first squadron in US military history to shoot down an enemy aircraft in early 1918.

By April 1918, the 1st Aero Squadron would be a part of the I Corps Observation Group, one of the first aviation groups focused specifically on collecting military intelligence from the skies. Each aero squadron consisted of 18 pilots, 18 observers and anywhere from 10-18 armorers. The I Corps Observation Group was primarily comprised of three squadrons: the 12th Aero Squadron flying French Dorand AR aicraft, the French 1st Squadron (soon to be replaced by the American 88th Aero Squadron flying British Sopwith’s) and the 1st Aero Squadron flying French SPAD airplanes.

SPAD XIII

SPAD XIII

Later in the war, the 1st Aero Squadron would receive the newer American-made Samson 2A2 airplanes, replacing the French SPAD’s.

Samson 2A2 w/ the 1st Aero Squadron, US Army Air Service

Samson 2A2 w/ the 1st Aero Squadron, US Army Air Service

The 1st Aero Squadron’s unique mission specifically consisted of the following efforts:

- Missions of a special nature request by the command

- Long-distance photographic missions

- Adjustment of divisional heavy artillery fire

- Long-distance visual reconnaissance

Around the time that Arnold was arriving in France in late June 1918, the I Corps Observation Group was in the midst of moving between areas of operation, leaving the Toul Sector and heading to the Marne sector to provide aerial observation in support of French troops along the Marne River. The efficiency of their move across France was notable:

During the last week of June, orders were received from the I Corps Observation Group headquarters, and the 1st and 12th Aero Squadrons proceeded to the Marne Sector. This move began on June 28, 1918, and by noon of the following day all the airplanes of both squadrons had been flown from Ourches and Vathemenil airdromes to the new field at Saints, three miles south of Coulommiers. Advance parties from each squadron arrive by automobile and completed the arrangements for quarters. By the evening of June 29, most of the I Corps Observation Groups' men and equipment had arrived at the new base and it was ready to begin operations.

American Air Service Observation in World War I by Sam Hager Frank, 1961

The 1st Aero Squadron would remain with the I Corps Observation Group for most of the war, first supporting US Marines at Château-Thierry followed by support of US Army operations along the Aisne and Marne Rivers and then in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, leading up to the end of the war. Although primarily an observation and reconnaissance squadron, the 1st Aero Squadron would still go on to record 13 aerial victories during the war, losing 16 pilots killed-in-action and an additional 3 pilots missing-in-action.

Life of an Armorer

During this time, Arnold’s work as an armorer with the 1st Aero Squadron likely would have been similar to the day-to-day activities described by 2nd Lt. R.H. Wessman, an Armament Officer with the 50th Aero Squadron:

There were 18 planes in the squadron besides a few extras. Each three planes were assigned to one armorer. He was responsible for the armament fixed on the planes, such as Marlin guns and ammunition, sights, tourelle, etc. He was responsible for keeping the gears filled with oil and taking the air out of the system. Also for going to the Armory for the Lewis guns and ammunition and putting them on the plane and taking them back to the Armory. There his responsibility increased in regards to the Lewis guns. One sergeant was in entire charge of all these men, and all armament in the hangars, so to speak.

One man was put in entire charge of the gears, to inspect them regularly and make any repairs which the ships’s armorers could not. The latter would take out the floor boards, etc., and prepare things for the C.C. gear man, who would in this way lose no time in getting around the ships.The U.S. Air Service in World War I, Volume IV, 1979

Wessman goes on to describe the overall organization of the Armor within the squadron:

Now we come to the Armory. A sergeant was in charge of everything therein. Under him there were six men, two corporals and four privates. One corporal specialized in Lewis guns, making any necessary repairs and preparing the guns, and shooting them before putting them on the planes. The other corporal specialized in Marlin guns. Under them are three helpers who clean Lewis guns and do the other necessary work round the Armory. One man tends entirely to the ammunition keeping individual pilot’s and observer’s ammunition straight, taking care and filling magazines, calibrating and getting together sets of Very pistol ammunition. There is one other man in the Armory who keeps records straight, keeps up supplies, takes down and posts the number of rounds fired, makes out reports, etc. So much for the organization. Let us now take, for example, a day in the Armory to show how the organization works.

The list of missions for the following day is obtained the night before, and is posted on a bulletin board so that the armorers may ascertain what work is in store for them. The armorers in the Armory then prepare the Lewis guns for early morning flight.

In the early morning every bit of armament is thoroughly inspected by those concerned. Marlin guns are cleaned, gears filled, air taken out, etc. In the Armory all the Lewis guns are cleaned superficially.The U.S. Air Service in World War I, Volume IV, 1979

And finally, Wessman describes the role of the armorer in preparing aircraft for a mission, and their role once it returns back to the field:

It is time for a mission. Three-quarters of an hour before hand, the Lewis guns are shot through and placed on a table, the ammunition and flares beside them. The armorer from the ship which is to go, comes in, gets the guns and ammunition and places them on the ship. He then tests the gears, wipes out the barrels of the Marlin guns, loads them, leaving them on safety.

When the ships come back, he gets the report of the number of rounds fired and troubles, if there were any, carries back the guns and ammunition, reports number of rounds fired to clerk and ammunition man. He goes back to his ship, cleans the guns and puts the armament in shape again. In the Armory the Lewis guns are cleaned and the magazines refilled.The U.S. Air Service in World War I, Volume IV, 1979

From the moment he joined their ranks in June 1918, through the armistice in November 1918 and later with the Army of Occupation after the end of the war into 1919, Arnold’s role as an armorer would have been vital in providing the observational airplanes of the 1st Aero Squadron the ability to defend themselves from enemy aircraft, allowing them to record vital military intelligence from the skies in support of the war effort.

Returning Home

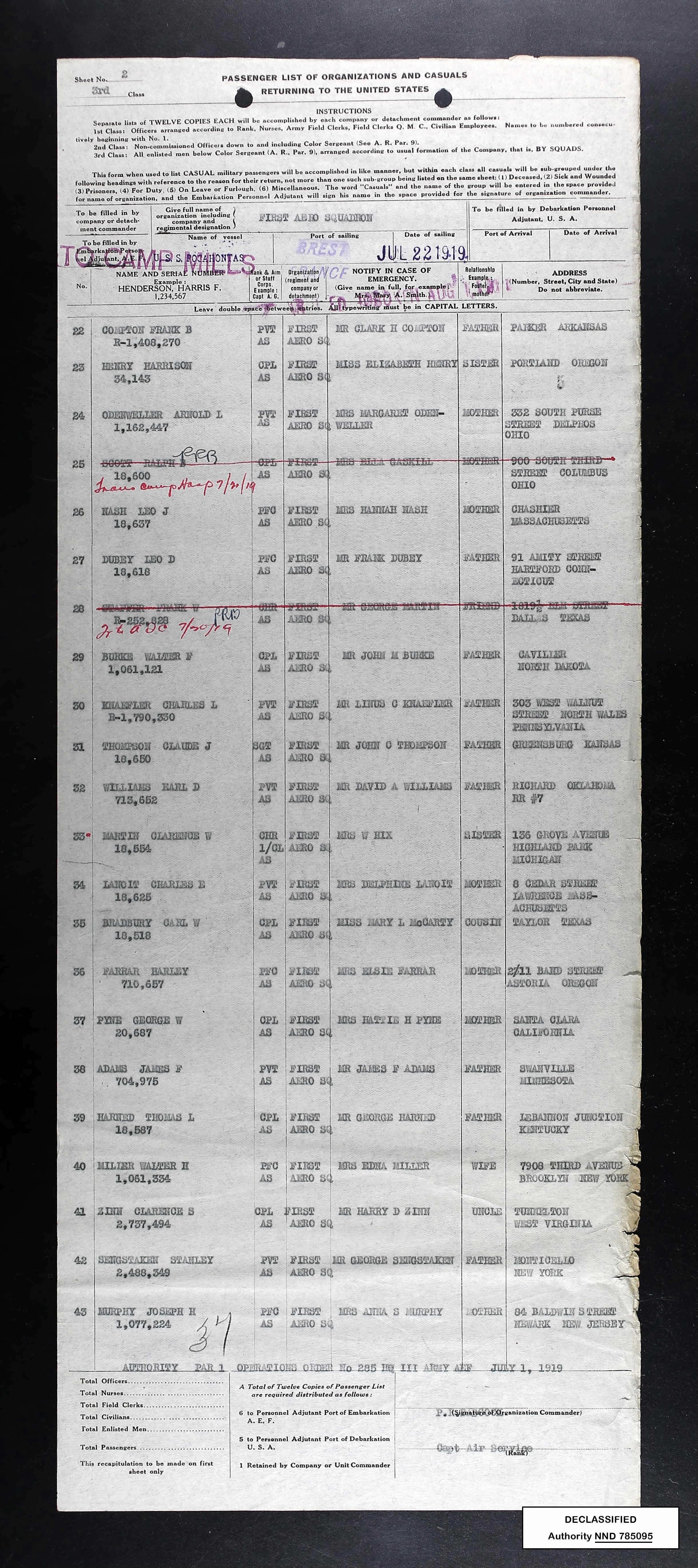

The 1st Aero Squadron would finally head home to the United States on July 22nd 1919, exactly a year and a month since first leaving her shores. Departing from the port city of Brest, France on the transport ship USS Pocahontas, the 1st Aero Squadron and Arnold would arrive in the harbors of New York City a few weeks later.

Returning to the United States, July 22nd 1918

Returning to the United States, July 22nd 1918

They would then eventually head to nearby Camp Mills, Long Island to be discharged from their military service, thus concluding Arnold’s role in World War I.

- Posted on:

- February 25, 2020

- Length:

- 14 minute read, 2949 words

- See Also: